Size in Square Kilometres

2,543

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Humpback whale – Megaptera novaeangliae

Criterion B(2); C (1,2,3)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Physeter macrocephalus, Tursiops truncatus, Ziphius cavirostris

Summary

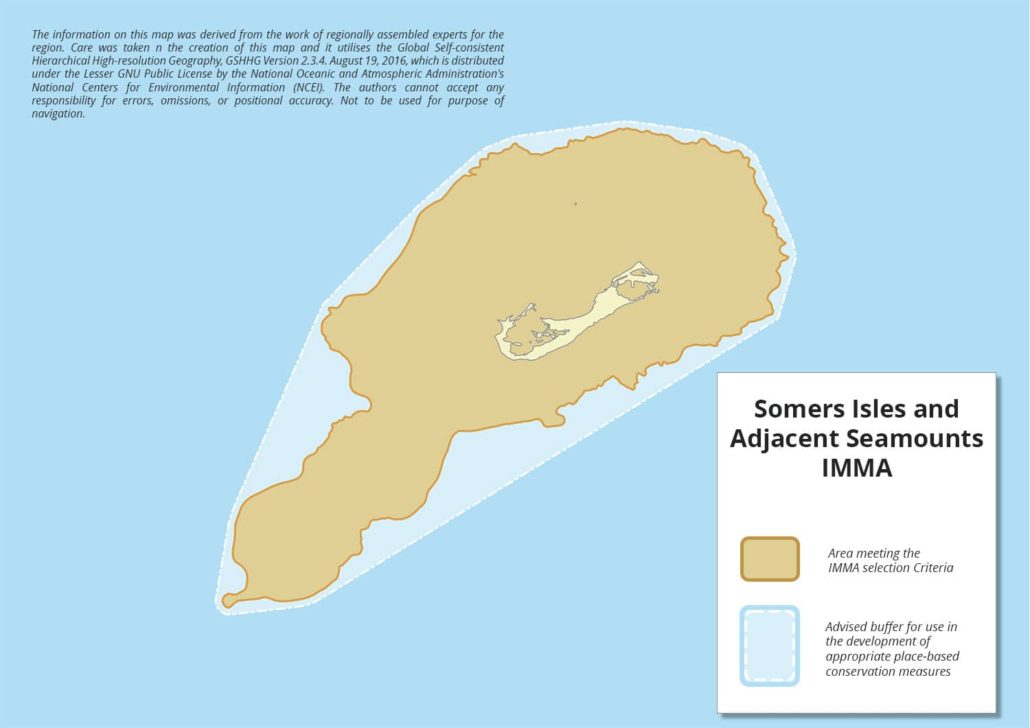

Bermuda, also known as the Somers Isles, is an isolated group of mid-oceanic islands. Located approximately 1,000km from the United States coastline, the IMMA includes shelf and deep waters closely following the steep 2,000m isobath of the Bermuda Platform around the two adjacent seamounts. While the Islands themselves cover 55 square kilometres, the IMMA area is approximately 3,097 square kilometres and contains two adjacent seamounts to the southwest of the Somers Isles, the Challenger and Argus Banks. The IMMA hosts seasonal aggregations of North Atlantic humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) that use the area as a stopover point on both the northern and southern migrations, as well as an important area for feeding, calving, and nursing young. Pilot and sperm whales also occur but these are presently not commonly observed. The waters around Bermuda were designated a Marine Mammal Sanctuary in 2012 and the IMMA is surrounded by, but not included in the Sargasso Sea Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Area described in 2012.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

Boat-based surveys since 2007 revealed the Somers Isles to be a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) migratory stopover ground (Grove et al., 2023), with whales observed passing through Bermuda waters on their way south to the Caribbean breeding/calving grounds from mid-December into February as well as on their way north from the breeding/calving grounds to their northern feeding grounds March through to mid-May. Peak aggregations occur from mid-March to late April. An abundance survey indicated some 1,000-2,000 humpbacks migrate through Bermuda, with reconstructed abundances showing exponential growth since 2012 (Grove et al. 2022, 2023). Numerous important habitats have been identified including areas for feeding, resting, using sand holes to remove parasites, and singing (Stevenson and Werth, 2024). It is believed that the complex topography of the canyon enhances song transmission (Payne and Payne, 1985). On their way north, large numbers of humpbacks aggregate in the IMMA, with layovers up to 21 days. Groups with over a dozen individuals can be observed milling around for many hours. Their behaviour differs from earlier in the season when competitive groups are frequently observed. These large groups will then suddenly move at a consistent speed and heading (north) with coordinated breathing in what appears to be a convoy.

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

From 2016 onwards, female humpback whales have been observed with very small calves from late December to early January (Stevenson et al. 2017; Stevenson 2019; 25 minutes 22 seconds). Notably in the early 20th century, calves 4.5 to 9.1 m in length were sighted until early June; from 1980-1985 and over 37 days of sighting effort, 6% of sightings were calves (Stone et al. 1987). These small calves could not have migrated to Bermuda from the Caribbean in December or early January, suggesting that some female humpbacks use Bermuda and the adjacent seamounts as birthing grounds on their southward migration (Kettemer 2023). Mothers with 3–4-month-old calves are also the last humpbacks to enter Bermuda’s waters in the latter part of April or early May. These calves can be observed nursing in shallow waters (Stevenson 2019; 19 minutes 07 seconds). From early to late March, male competitive groups are observed chasing females, with males engaged in fierce fighting such as swimming on top of another male to prevent it from surfacing, and slashing pectoral fins at one another (Stevenson 2019; 22 minutes, 48 seconds to 25 minutes 20 seconds). Aerial footage reveals competitive groups of as many as 25 whales chasing and fighting over a single female (Stevenson 2019; 22 minutes 48 seconds to 25 minutes 20 seconds).

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

Systematic boat-based surveys conducted from 2007 onward by WhalesBermuda have observed humpback whales foraging on the edges of the Bermuda Platform and adjacent seamounts, particularly Sally Tuckers and the windward edge of Challenger Bank (Stevenson 2011). Humpback whales are thought to be diving at dusk and overnight to feed on the deep scattering layer in this area where there are also signs of defecation (Stone et al. 1987; Hamilton et al. 1997). Recent boat-based photos of defecation episodes while tail lobbing, together with aerial footage and collected faecal samples provide additional evidence of regular feeding in the IMMA. Bermuda and its adjacent seamounts are thought to provide an important stopover ground (Grove et al. 2023) and feeding station, providing opportunistic feeding opportunities to whales before they migrate north (Stone et al. 1987; Katona and Beard 1990). DNA sequencing of solid faecal specimens indicate krill (Thysanopoda) and bristlemouth fish (Cyclothone) are important to humpback diets in the area (A. Stevensen and L. Blanco Bercial, unpublished data).

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

Bermuda is one of the only areas in the North Atlantic where humpback whales are regularly observed during migration (Stone et al. 1987), with some individuals exhibiting strong fidelity to Bermuda (Beaudette et al. 2009). Photo identification and passive acoustic monitoring indicate that humpback whales are present in from mid-December to mid-May (Narganes Homfeldt et al. 2022), and densities in the IMMA are highest when whales are on their southerly route mid-December and again in early March as they migrate northwards. Modelled annual abundance estimated between 1,000-2,000 humpbacks migrate over the Bermuda Platform and adjacent seamounts (Grove et al. 2022, 2023), with 13% of humpbacks recorded across multiple years (Grove et al. 2023). Residency times based on photo-identification usually do not exceed three weeks, and updated photo identifications of 2,327 humpback whales suggest Bermuda and its adjacent seamounts are migratory stopover grounds (Grove et al. 2023) before continuing their journey north to the feeding grounds. The layovers of multiple days in Bermuda waters on similar dates year-to-year emphasises the hypothesis that Bermuda and its adjacent seamounts are not simply transitory migratory corridors (Grove et al. 2023). WhalesBermuda and others have matched whales in Bermuda to whales in the Caribbean, the eastern United States and Canada, and as far northeast as Franz Josef Land in Russia, Iceland, Ireland, Greenland, and the Azores (Stone et al. 1987).

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

Supporting Information

Angel, M. 2011. The pelagic ocean assemblages of the Sargasso Sea around Bermuda. Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series, No. 1, 25 pp.

Beaudette, A., Allen, J., Bort, J., Stevenson, A., Stevick, P. and Stone, G. 2009. Poster presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 18th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Quebec City, Canada, 12-16 October 2009.

Coates, K.A., Fourqurean, J.W., Kenworthy, W.J., Logan, A., Manuel, S.A. and Smith, S.R. 2013. Introduction to Bermuda: geology, oceanography and climate. In Coral reefs of the United Kingdom overseas territories. Pp.115-133. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Fahlman, A., Tyson Moore, R.B., Stone, R., Sweeney, J., Trainor, R.F., Barleycorn, A.A., McHugh, K., Allen, J.B. and Wells, R.S. 2023. Deep diving by offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.). Marine Mammal Science 39:1251-1266.

Grove, T., King, R., Stevenson, A., and Henry, L.-A. 2023. ‘A decade of humpback whale abundance estimates at Bermuda, an oceanic migratory stopover site’. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9:971801. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.971801.

Fawcett, S. E., Lomas, M.W., Ward, B.B. and Sigman, D.M. 2014. The counterintuitive effect of summer-to-fall mixed layer deepening on eukaryotic new production in the Sargasso Sea. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 28:86–102.

Grove, T., King, R., Henry, L.-A. and Stevenson, A. 2022. Modelled annual abundance of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae around Bermuda, 2011-2020. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.945442.

Grove, T., King, R., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2023. A decade of humpback whale abundance estimates at Bermuda, an oceanic migratory stopover. Frontiers in Marine Science 9:971801.

Ham, J.R., Lilley, M.K. and Manitzas Hill, H.M. 2023. Non-conceptive sexual behavior in cetaceans: comparison of form and function. In: Würsig, B., and Orbach, D.H. (eds.) Sex in Cetaceans: Morphology, Behavior, and the Evolution of Sexual Strategies, pp.129-152. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Hay, C., Henry, L.-A., Roberts, J.M. and Stevenson, A. 2024. Spatial layers examining whether a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area can be justified in Bermuda to aid in cetacean conservation. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.961168.

Katona, S.K. and Beard, J.A. 1990. Population size, migrations and feeding aggregations of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 12, pp.295-306.

Kettemer, L.E. 2023. Migration ecology of North Atlantic humpback whales: mapping movements throughout the annual cycle. PhD thesis, Arctic University of Norway.

Klatsky, L.J., Wells, R.S. and Sweeney, J.C. 2007. Offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Movement and dive behavior near the Bermuda Pedestal. Journal of Mammalogy 88:59-66.

Narganes Homfeldt, T., Risch, D., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2022a. Seasonal and diel patterns in singing activity of humpback whales migrating through Bermuda. Frontiers in Marine Science 9:941793.

Narganes Homfeldt, T., Risch, D., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2022b. Spectrograms of singing humpback whales migrating through Bermuda. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.946517.

Payne, K. and Payne, R. 1985. Large scale changes over 19 years in songs of humpback whales in Bermuda. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 68:89-114.

Stevenson, A. 2011. Humpback whale research project, Bermuda. Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series, No 11, 11pp. ISBN 978-0-9892577-3-2.

Stevenson, A. 2019. The Secret Lives of the Humpbacks. Directed by Andrew Stevenson, Bermuda. https://vimeo.com/354733042.

Stevenson, A. Forthcoming. Observation dates of Cuvier’s beaked whales and bottlenose dolphins around Bermuda. Report to the Sargasso Sea Commission.

Stevenson, A., Rigaux, C., Stringer, C., van de Weg, R. and Clee, J. 2017. The secret mid-ocean lives of humpback whales: pelagic social behaviour of North Atlantic humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) evidenced by 1500+ fluke IDs plus underwater and aerial footage. Poster presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Halifax, Canada, 23-27 October, 2017.

Stevenson, A. and Werth, A. 2024. Humpback whales inflate pleated oral pouch to scratch an itch and detach parasites. Marine Mammal Science e13127.

Stone, G.S., Katona, S.K. and Tucker, E.B. 1987. History, migration and present status of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae at Bermuda. Biological Conservation 42:133-145.

Wells, R.S., Fahlman, A., Moore, M., Jensen, F., Sweeney, J., Stone, R., Barleycorn, A., Trainor, R., Allen, J., McHugh, K., Brenneman, S., Allen, A., Klatsky, L. and Douglas, D. 2017. Bottlenose dolphins in the Sargasso Sea – Ranging, diving, and deep foraging. Oral presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Halifax, Canada, 23-27 October, 2017.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Somers Isles and Adjacent Seamounts IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile and/or geojson) for the Somers Isles and Adjacent Seamounts IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: