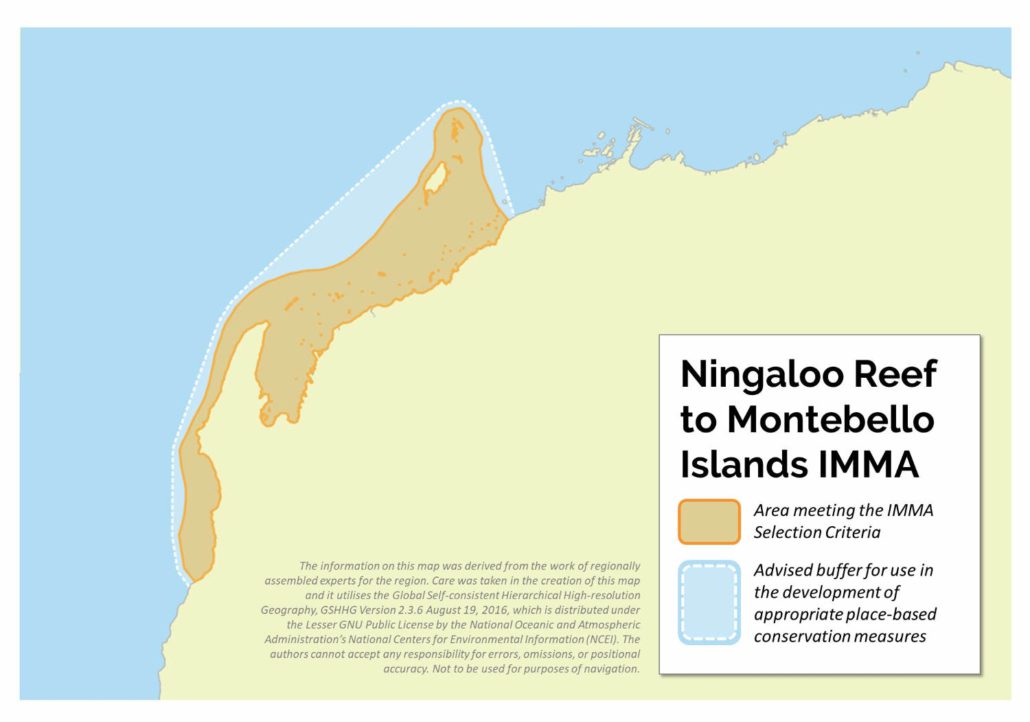

Size in Square Kilometres

18,437

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Dugong – Dugong dugon

Criterion A; B (1); C (2)

Australian humpback dolphin – Sousa sahulensis

Criterion A; B (1)

Humpback whale – Megaptera novaeangliae

Criterion C (1)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Balaenoptera musculus, Balaenoptera omurai, Balaenoptera physalus, Eubalaena australis, Orcaella heinsohni, Orcinus orca, Pseudorca crassidens, Tursiops aduncus

Summary

The Pilbara region of Western Australia encompasses a variety of marine habitats including coral reef, coastal islands and a large sheltered embayment that support several populations of marine mammals. This area has been recognized at a national and international level through designation of State and Commonwealth marine protected areas and the Ningaloo Coast World Heritage Area. The sheltered waters of Exmouth Gulf are an important feeding and nursing/calving habitat for Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis), dugongs (Dugong dugon), and Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) and an important nursery area for humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). The waters around Ningaloo Reef are similarly important to migrating humpback whales and resident populations of humpback and Indo-pacific bottlenose dolphins. The Pilbara region is characterized by numerous coastal and offshore islands, which provide habitat for coastal dolphin species and dugongs. Omura’s whales, killer whales, false killer whales, southern right whales, blue whales and Australian snubfin dolphins have all been sighted across this region.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

Dugongs (Dugong dugon) and Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis) are both listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN and are resident to the region (Hunt 2018, Hunt et al., 2017, Allen et al., 2012, Hodgson 2007, Sobtzick et al., 2014, Bayliss et al., 2018, Marsh and Sobtzick 2019). Furthermore, this area has been recognized at a national and international level through designation of State and Commonwealth marine protected areas including Ningaloo Marine Park and Murion Islands Management Area, Barrow Island Marine Park and Montebello Islands Marine Park as well as the Ningaloo Coast World Heritage Area.

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

The coastal waters of the North West Cape and Exmouth Gulf support resident populations of Vulnerable Australian humpback dolphins and Near Threatened Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. Australian humpback dolphins inhabit the area with the highest density recorded for this species around North West Cape, with a population size estimated at 129 individuals within a 130 km2 area (Hunt et al 2017). Haughey et al. (2020) estimated a resident population of 141 (95% CI 121-161) Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins at the North West Cape, highlighting the importance of these coastal waters. Resident populations have also been recorded along the Pilbara coast and islands (Hanf 2015, Raudino et al 2018a) though no abundance estimates have been made. There are early indications that the dolphins inhabiting island habitat may be geographically separate from the mainland coastal population (Raudino et al 2018b). In particular high levels of female residency in humpback dolphins (Hunt et al., 2019) suggest that these waters are important for breeding and nursing for this species and dolphin calves were sighted during this study (Hunt 2017). Exmouth Gulf also contains a significant population of Vulnerable dugongs with estimates fluctuating over the years; 1062 (±321) individuals in 1989, 95 (±62) individuals in 2000, 1411 (±561) in 2007 and 4,599 ( 1,959) in 2018 (Preen et al 1997, Prince 2001, Hodgson 2007, RPS 2010, Bayliss et al 2019). Variation in dugong abundance and use of the Exmouth Gulf is likely a result of the seagrass loss following tropical cyclones and marine heatwaves and movement of dugongs to areas supporting seagrass (Bayliss et al 2019, Gales et al 2004). Aerial surveys of dugongs between 1989 and 2018 consistently identify the nearshore eastern waters of the Gulf as critical feeding and nursing habitat (Preen et al 1997, Bayliss et al 2019). Local-scale drone surveys coupled with in-situ assessments of the benthic habitat have shown that seagrass, particularly Halophila and Halodule species, are significant factors influencing dugong presence in south-eastern Exmouth Gulf (Christophe Cleguer pers comm).

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

The sheltered waters of Exmouth Gulf have been suggested to have contributed to the recovery of the Breeding Stock D humpback whale population. The Gulf is the largest known resting area for this population, initially from 1950’s whaling data (Chittleborough, 1953) and more recently from boat-based and aerial surveys that report resting behaviour occurring (Jenner et al., 2001, Jenner and Jenner 2005, Braithwaite et al., 2012, Irvine and Salgado Kent 2019), where mothers and calves can spend up to 3 weeks (Jenner & Jenner, 2005) resting and gaining size and strength. In addition, the area represents a southward extension of the breeding grounds for calving and mating (Irvine et al., 2018).

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

The seagrass habitat of Exmouth Gulf is an important feeding ground for dugongs. Aerial surveys of dugongs between 1989 and 2018 consistently identify the nearshore eastern waters of the Gulf, Pilbara coastal waters and nearshore Pilbara islands as critical feeding and nursing habitat (Sobztick et al 2014, RPS 2010). Local-scale drone surveys coupled with in-situ assessments of the benthic habitat have shown that seagrass species such as Halophila and Halodule are good predictors of dugong presence and abundance in the south-east Gulf (Christophe Cleguer pers. comm.). Variation in dugong abundance and use of Exmouth Gulf and the broader Pilbara Region is likely a result of the seagrass loss following tropical cyclones and marine heatwaves and movement of dugongs to areas supporting seagrass (Gales et al 2004, Sobztick et al 2014). Safeguarding the seagrass in the Gulf will protect a feeding ground and allow dugongs to migrate from alternative feeding grounds when required.

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

Supporting Information

Allen, S.J., 2012. Tropical inshore dolphins of north-western Australia: Unknown populations in a rapidly changing region. Pacific Conservation Biology 18: 56-63.

Bayliss, P., H. Raudino, and M. Hutton, Dugong (Dugong dugon) population and habitat survey of Shark Bay Marine Park and Ningaloo Reef Marine Park, and Exmouth Gulf. 2018.Report to the National Environmental Science Program prepared by CSIRO and Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. p. 51.

Bayliss, P., et al. 2019. Modelling the spatial relationship between dugong (Dugong dugon) and their seagrass habitat in Shark Bay Marine Park before and after the marine heatwave of 2010/11. Final Report to the National Environmental Science Program prepared by CSIRO and Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. p. 55.

Bejder, L., et al., Low energy expenditure and resting behaviour of humpback whale mother-calf pairs highlights conservation importance of sheltered breeding areas. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1).

Braithwaite, JE, Meeuwig, JJ, Jenner, KCS (2012) Estimating Cetacean Carrying Capacity Based on Spacing Behaviour. PLoS ONE 7, e51347.

Chittleborough, R.G. 1953. ‘Aerial observations on the humpback Chittleborough, R.G. 1953. ‘Aerial observations on the humpback whale Megaptera nodosa (Bonnaterre), with notes on other species’. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 4:219-226.

Fitzpatrick, B., et al. 2019. Exmouth Gulf, north Western Australia: A review of environmental and economic values and baseline scientific survey of the south western region. 2019, Report to the Jock Clough Marine Foundation. p. 192pp.

Gales, N., et al. 2004. Change in abundance of dugongs in Shark Bay, Ningaloo and Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia: evidence for large-scale migration. Wildlife Research, 2004. 31(3): p. 283-290.

Hanf, D.M. 2015. Species distribution modelling of Western Pilbara inshore dolphins. Murdoch University. Masters thesis, 130pp.

Haughey, R., et al., Photographic capture-recapture analysis reveals a large population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) with low site fidelity off the North West Cape, Western Australia. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2020.

Hodgson, A. 2007. The distribution, abundance and conservation of dugongs and other marine megafauna in Shark Bay Marine Park, Ningaloo Reef Marine Park and Exmouth Gulf. James Cook University, Townsville.

Hunt, T. et al. in review. Identifying priority habitat for conservation and management of Australian humpback dolphins within a marine protected area. Scientific Reports.

Hunt, T., et al., 2017. Demographic characteristics of australian humpback dolphins reveal important habitat toward the southwestern limit of their range. Endangered Species Research. 32: p. 71-88.

Hunt, T.N., Demography, habitat use and social structure of Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis) around the North West Cape, Western Australia: Implications for conservation and management. 2018, Flinders University: Adelaide, Australia.

Irvine, L.G., Thums, M., Hanson, C.E., McMahon, C.R. and Hindell, M.A. 2018. ‘Evidence for a widely expanded humpback whale calving range along the Western Australian coast’. Marine Mammal Science, 34(2): 294-310.

Irvine, L. and C. Salgado-Kent,. 2019. The distribution and relative abundance of marine-megafauna, with a focus on humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), in Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia, 2018. Report to the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions.

Jenner, K.C.S., M.N.M. Jenner, and K.A. McCabe. 2001. Geographical and temporal movements of humpback whales in Western Australian waters. APPEA Journal, p. 749-765.

Jenner, C. and Jenner, M.N. 2005. ‘Distribution and abundance of humpback whales and other mega-fauna in Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia, during 2004/2005’. Final Report prepared for Straits Salt Pty. Ltd.

Kiszka, J., Méndez-Fernandez, P., Heithaus, M. R., Ridoux, V. 2014. “The foraging ecology of coastal bottlenose dolphins based on stable isotope mixing models and behavioural sampling.” Marine Biology 161(4): 953-961.

Marsh, H. & Sobtzick, S. 2019. Dugong dugon (amended version of 2015 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T6909A160756767. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T6909A160756767.en.

Ottewell, K., et al. 2016. A recent stranding of Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) in Western Australia. Aquatic Mammals, 2016. 42(2): p. 193-197.

Pitman, R.L., et al. 2015. Whale killers: Prevalence and ecological implications of killer whale predation on humpback whale calves off Western Australia. Marine Mammal Science, 31(2): p. 629-657.

Preen, A.R., 1997. Distribution and Abundance of Dugongs, Turtles, Dolphins and other Megafauna in Shark Bay, Ningaloo Reef and Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia. Wildlife Research, 24(2): p. 185-208.

Prince, R.I.T. 2001. ‘Aerial survey of the distribution and abundance of dugongs and associated macroinvertebrate fauna – Pilbara coastal and offshore region, WA’.

Raudino H, Douglas C, Waples K. 2018a. How many dolphins live near a coastal development? Regional Studies in Marine Science. 19:25-32.

Raudino H., Hunt T., Waples, K. 2018b. ‘Records of Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis) from an offshore island group in Western Australia’. Marine Biodiversity Records, 11:14-20.

RPS. 2010. Nearshore Regional Survey Dugong Report, in Browse Liquefied Natural Gas Precinct Strategic Assessment Report.

Salgado-Kent, C., et al. 2012.Southern hemisphere breeding stock ‘D’ humpback whale population estimates from North West Cape, Western Australia. . Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 12: p. 29-38.

Salgado Kent, C. 2019. Distribution, abundance and residency of humpback whales in Bateman Bay in Ningaloo Marine Park, Western Australia. Report prepared for DBCA. pp 63.

Sobtzick, S., Hodgson, A.J., Campbell, R., Smith, J.N. and Loneragan, N. 2014. Chevron Wheatstone Project Dugong Research Program: Phase 2, 2013 Final Report. A report prepared by Murdoch University Cetacean Research Unit and James Cook University, for Chevron Pty Ltd.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Ningaloo Reef to Montebello Islands IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile and/or geojson) for the Ningaloo Reef to Montebello Islands IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: