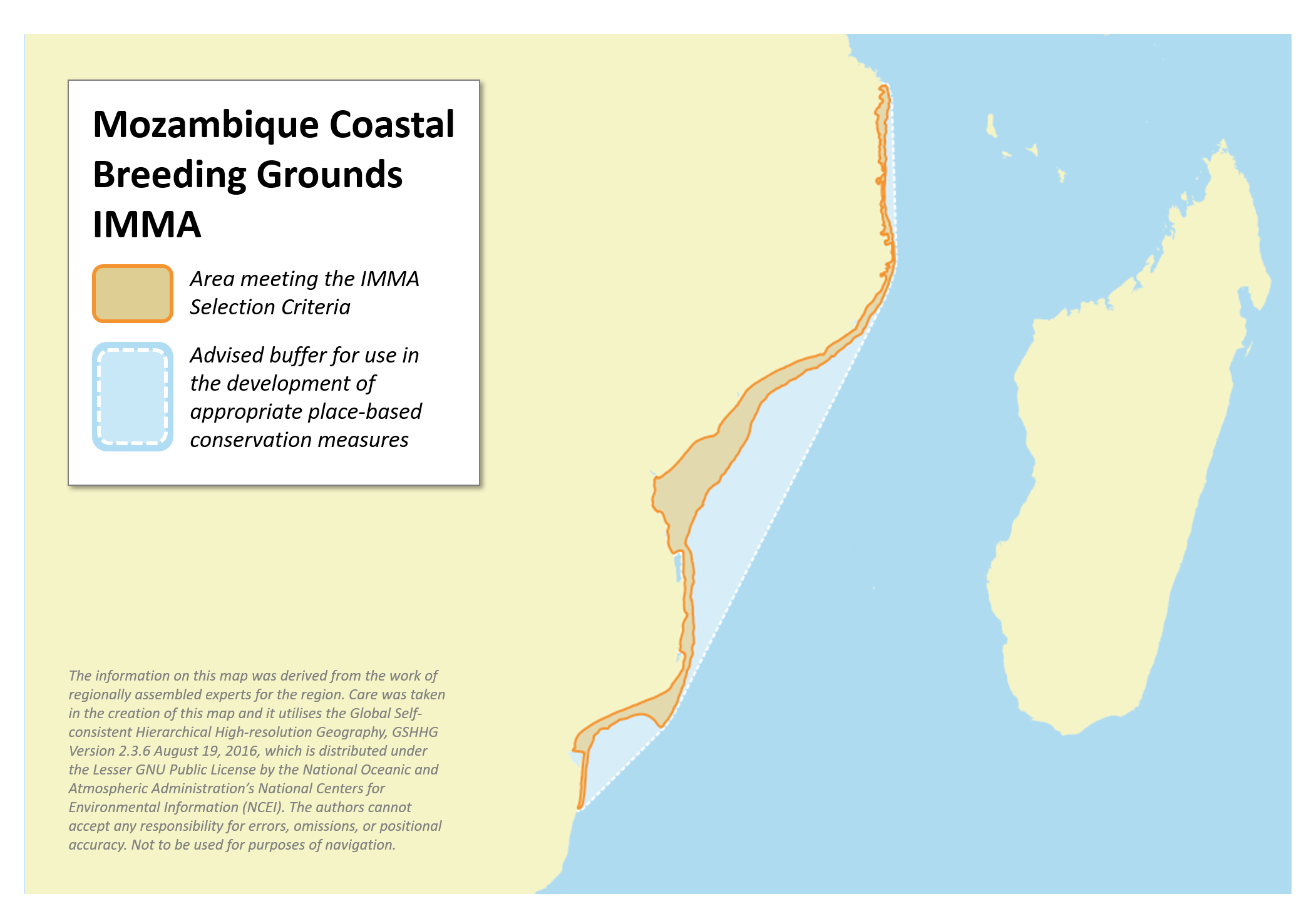

Mozambique Coastal Breeding Grounds IMMA

Size in Square Kilometres

80 936 km2

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Humpback whale – Megaptera novaeangliae

Criterion C (1)

Marine Mammal Diversity

Delphinus delphis, Eubalaena australis, Megaptera novaeangliae, Orcinus orca, Sousa plumbea, Stenella longirostris, Tursiops aduncus

Download fact sheet

Summary

Between the months of July and November each year, the coastal waters of Mozambique are utilised as a mating, calving and nursery ground for Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Male whales in this area have been recorded singing and observed in competitive groups, and mother-calf pairs are observed throughout the IMMA from the southern border with South Africa to the northern border with Tanzania. Both of the broad shelf regions of southern and central Mozambique, including the Sofala Banks, appear to be priority calving areas. Although the population using this breeding ground appears to be increasing at a healthy rate, this African east coast mainland Breeding Stock (labelled the ‘C1 stock’ by the International Whaling Commission) appears discrete from the other breeding Stocks in the Western Indian Ocean and was heavily targeted by land based whaling operations between 1908 and 1917.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1: Reproductive Areas

The coastal waters (between the 20m-200m isobaths) of Mozambique are utilised as a mating, calving and nursery ground between July and November each year by the C1 South sub-stock of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) (as recognised by the IWC). Catches from Linga-linga, Mozambique, were unimodal in seasonal abundance with peak catches in August or July (Lea, 1919; Olsen, 1914; Best et al., 1998).The abundance of whales on this ground was estimated (Maputo to Quelimane) at 1954 (CV 0.38) in 1991 (Findlay et al., 1994) and 5,930 (CV = 0.15) in 2003 (Findlay et al. 2011a). The 1991 survey found humpback whales distributed over the entire survey region, although densities were highest between 33°E and 35°30’E (Maputo to Ponta Zavora) over a region of shallow banks (where the southerly Mozambique Current flowed further offshore) and a high density of cow and calf pairs were recorded on the Sofala Banks. Higher than expected sighting frequencies were recorded on the 2003 survey in the regions between Cabo Inhaca and Xai-Xai, between Ponta Zavora and Bazaruto and in the region of the Pantaloon Shoals to the north east of Quelimane, while lower than expected sighting frequencies were recorded over the Sofala Banks (although these densities may be influenced by survey conditions). Cow and calf groups were distributed throughout the survey area. Incidental reports suggest the extensions of this breeding behaviour to the northern Mozambique border. No data are available to identify humpback breeding behaviour outside of the 200m isobath, but evidence from other breeding grounds suggest this would be unlikely. Despite some photo-identified movement of individuals between Mozambique waters and South African waters, available photo-identification information suggests limited movement between the Mozambique and other Western Indian Ocean coastal breeding areas (for example Madagascar). Such limited exchange is supported by the timing of catch records (Findlay, 2001) and by genetic analyses (Rosenbaum et al., 2009). After severe depletion due to modern whaling between 1908 and 1963 (with few individuals possibly taken from this sub-stock thereafter by Soviet fleets until 1973) (Findlay, 2001), the population has been shown through shore-based monitoring of the migration corridor to be increasing at over 9% per annum (Findlay et al., 2011b). Comparison of distance-based densities suggest a similar considerable increase in the population between the 1991 and 2003 surveys.

Supporting Information

Best, P.B., Findlay, K.P., Sekiguchi, K., Peddemors, V.M., Rakotonirina, B., Rossouw, A., and Gove, D. 1998. ‘Winter distribution and possible migration routes of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae in the southwest Indian Ocean.’ Marine Ecology Progress Series,162: 287-299.

Findlay, K.P. 2001. ‘A review of humpback whale catches by modern whaling operations in the Southern Hemisphere.’ Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 47(2): 411-420.

Findlay, K.P. et al. (9 authors) 2011a. ‘Distribution and abundance of humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, off the coast of Mozambique.’ Journal of Cetacean Research and Management Special Issue 3: 163-174.

Findlay, K. P., Best, P. B., and Meÿer, M. A. 2011b. ‘Migrations of humpback whales past Cape Vidal, South Africa, and an estimate of the population increase rate (1988–2002).’ African Journal of Marine Science 33(3): 375–392.

Findlay, K.P., Best, P.B., Peddemors, V.M. and Gove, D. 1994. ‘The distribution and abundance of humpback whales on their Mozambique winter grounds.’ Reports of the International Whaling Commission, 44: 311-320.

IWC. 1998. ‘Report of the Scientific Committee. Annex G. Report of the sub-committee on Comprehensive Assessment of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales’. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, 48, 170-182.

Lea, E. 1919. Studies on the modern whale fishery in the Southern Hemisphere. (unpublished), Bergen, Norway. 95 + tables and mapspp. Unpublished manuscript in British Museum (Nat. Hist.) files. Handwritten note on cover says `received by the Falklands Islands Committee’.

Olsen, O. 1914. Hvaler og hvalfangst I Sydafrika. Bergens Museum Aarbok, 1914-1915, 1-56.

Rosenbaum, H.C., Pomilla, C.C., Mendez, M.C., Leslie, M., Best, P., Findlay, K., Minton, G., Ersts, P., Collins, T., Engel, M., Bonatto, S., Kotze, D., Meÿer, M., Barendse, J., Thornton, M., Razafindrakoto, Y., Ngouessono, S., Vely, M., and Kiszka, J. 2009. ‘Population structure of humpback whales from their breeding grounds in the South Atlantic and Indian oceans.’ PLoS ONE 4: e7318.