Size in Square Kilometres

353,457

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Sperm whale – Physeter macrocephalus

Criterion A; B (1)

West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus – T.m. manatus and T.m. latirostris)

Criterion A; D (1)

Atlantic Spotted dolphin – Stenella frontalis

Criterion B (1)

Common Bottlenose Dolphin – Tursiops truncatus

Criterion B (1)

Goose-beaked whale – Ziphius cavirostris

Criterion B (2); D (1)

Dwarf Sperm Whale – Kogia sima

Criterion B (2)

Melon-headed Whale – Peponocephala electra

Criterion B (2)

Pygmy Sperm Whale – Kogia breviceps

Criterion B (2)

Humpback Whale – Megaptera novaeangliae

Criterion C (1)

Blaineville’s Beaked Whale – Mesoplodon densirostris

Criterion B (1); D (1)

Gervais’ Beaked Whale – Mesoplodon europaeus

Criterion D (1)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Globicephala macrorhynchus, Grampus griseus, Kogia breviceps, Kogia sima, Lagenodelphis hosei, Megaptera novaeangliae, Mesoplodon densirostris, Mesoplodon europaeus, Orcinus orca, Peponocephala electra, Physeter macrocephalus, Stenella attenuata, Stenella frontalis, Steno bredanensis, Trichechus manatus, Tursiops truncatus, Ziphius cavirostris

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Balaenoptera edeni, Balaenoptera physalus, Delphinus delphis, Feresa attenuata, Pseudorca crassidens, Stenella clymene, Stenella coeruleoalba, Stenella longirostris longirostris

Summary

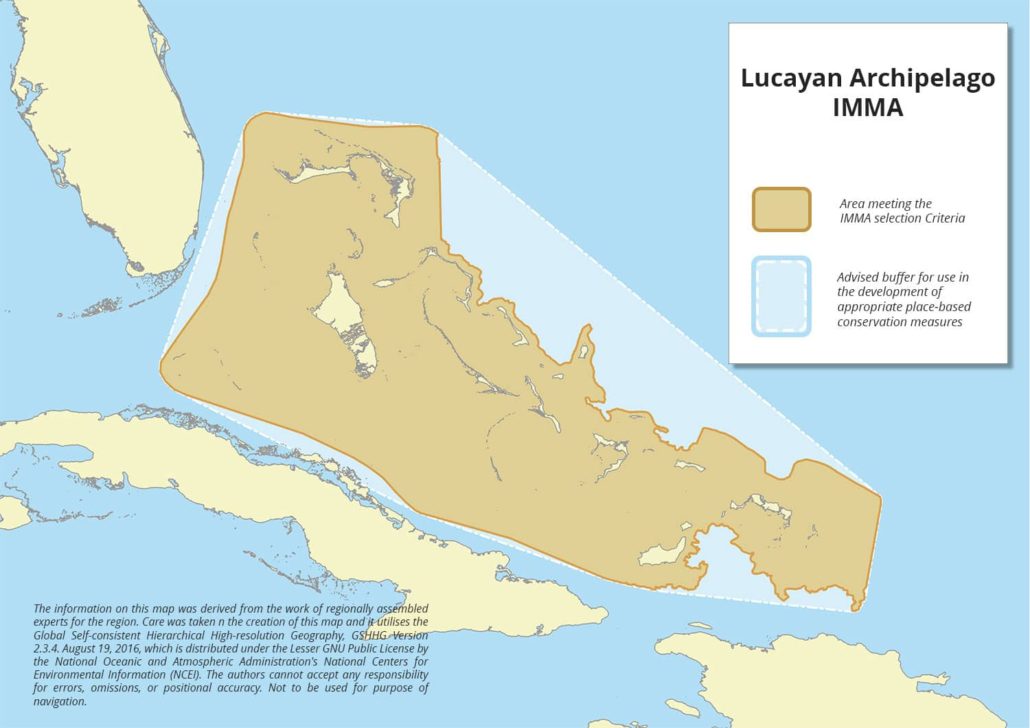

The Lucayan Archipelago is located east of Florida and north of the Greater Antilles and includes all the islands of The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. The IMMA includes the coastal area inhabited by the two endangered subspecies of manatees, Greater Caribbean/Antillean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus) and Florida manatees (T. m. latirostris). The network of carbonate banks which define the islands are home to resident communities of Atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis) and common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and are used by breeding humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). This area also includes three submarine canyons (Great Bahama Canyon, Little and Great Abaco Canyons) which aggregate deep-diving species, including three species of beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris, Mesoplodon europaeus, and Mesoplodon densirostris), melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra), and Vulnerable sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). This area includes a number of marine protected areas in the region as well as designated EBSAs. This area sustains a high diversity of marine mammals (totaling 26 species, of which 17 occur regularly).

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

Several small and resident communities of Atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis) and common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) have been studied for more than 25 years in several sites across the carbonate bank system of the Bahamas Archipelago (Claridge, 1994; Dudzinski, 1996; Herzing, 1991, 1997; Brunnick, 2000; Rogers et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2006; Fearnbach et al., 2011, 2012; Elliser and Herzing, 2012, 2014, 2016; Muller, 2020; Danaher-Garcia, 2020; Coxon et al., 2022).

Since 1991, annual immigration rates into the community of Atlantic spotted dolphins on the Little Bahama Bank were low (around 2%, Elliser and Herzing, 2012), with new births accounting for the majority of increases in the population, suggesting a small and resident population with social divisions across sites (Elliser and Herzing, 2012, 2014, 2016). A 6-year photo-identification study of Atlantic spotted dolphins at one study site on Little Bahama Bank (White Sand Ridge) reported 63% of 89 individuals identified were resighted in every year of the study, suggesting high site fidelity of a small population (Elliser and Herzing, 2014). A stranded adult Atlantic spotted dolphin, rehabilitated and then fitted with a satellite tag before release, returned to the location where this dolphin was known to researchers for 8 years prior to stranding (Dunn et al., 2017), further demonstrating how site faithful this species is in The Bahamas.

Genetic studies of the population structure of common bottlenose dolphins in the northern Bahamas corroborate site fidelity documented through long-term photo-identification studies (Claridge 1994; Parsons et al., 2006; Durban et al., 2000; Coxon et al., 2022). Abundance estimates and population demographics are available for two of these subpopulations, both in the NE Bahamas, and both in decline. Using photo-identification data from 1992–2010 and an open-population model that allowed animals to move in and out of the study area over time, Fearnbach et al. (2012) reported a core resident population in East Abaco with high multi-year site fidelity and a larger population that was more “transient” in their use of the area. During the study period, the resident population decreased from a high of 47 dolphins in 1996 to 24 dolphins by 2009. This decline was explained by mortality exceeding recruitment (births) in all years since 1996. Similarly, the larger population also declined from an estimated high of 187 dolphins in 1996 to a low of 96 in 2009. In South Abaco, Webber (2018) fitted a mark-recapture model to photo-identification data from 2000–2014 using a Robust Design approach and reported a small declining population. Estimates of abundance in South Abaco decreased from 63 individuals in 2002 to 34 in 2012, and management and conservation strategies were recommended to protect this small and vulnerable population (Webber 2018). Coxon et al. (2022) estimated birth rate and age-class-specific apparent survival rates for the South Abaco population using photo-identification data from 1997–2014. This study confirmed the existence of a core adult population with relatively high site fidelity in South Abaco and also evidence of transient animals. Notably, this study found strong support for a decline in apparent survival for all age-classes, with a decline of 36% in calves (0.970 to 0.606; 1997-2013, Coxon et al. 2022) best explained by repeated hurricane activity leading to increased mortality.

Off the Turks and Caicos Islands, small resident pods (and nursery groups) of common bottlenose dolphins and Atlantic spotted dolphins have been encountered (Hart and Bacon, 2022; Turks and Caicos Islands Whale Project unpublished data). Although the numbers are low on the Turks Bank, the occurrence and distribution of these species are just now beginning to be studied off the Turks and Caicos Islands, and population data is not available at this time.

Blainville’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon densirostris) show a remarkable level of site fidelity to study sites within the IMMA (Claridge et al., 2012, 2015). For example, in the Great Bahama Canyon, multiple lines of evidence indicate long-term site fidelity of Blainville’s beaked whales to small (<200 km linear range) study areas (Claridge et al., in prep). Satellite telemetry (n = 21 tags, 3579 locations) showed limited dispersion from the tagging site of typically <100 km during tag durations up to 89 days. Even after displacement during navy exercises using sonar, the median distance that whales moved from the tagging site was 16.4 km and the maximum distance was 244 km. Photo-identifications collected during boat-based encounters between 1991 and 2016 documented that individuals of both sexes were repeatedly re-sighted over time, in some cases for over a decade. Of the 277 whales photo-identified, only six moved out of the study area, and these movements were to adjacent study sites <300 km away. Genetic relatedness, inferred from remote biopsy samples and stranded specimens, was significantly higher between individuals sampled within a study area than between areas, suggesting multi-generational site fidelity over small geographic ranges. Extensive longitudinal photo-identification data for Blainville’s beaked whales exist at two study sites in the northern Bahamas: South Abaco and the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) range, where 51% and 45% of individuals were re-identified across multiple years, respectively (Claridge et al., in prep). At the South Abaco site, where the time series is longest, philopatry of males and females has been described (Claridge 2013, Claridge et al., in prep). At the South Abaco site, an open population mark recapture model that allowed heterogeneity in capture probability by age/stage and sex class was fit to photo-identification data collected from 1997 to 2011. Average annual abundance was 43 whales (95% HPDI, 35 - 57, Claridge 2013). At AUTEC, Blainville’s beaked whales are regularly detected acoustically on AUTEC’s 500 km2 hydrophone array (Moretti et al. 2006; DiMarzio et al., 2008; Hazen et al. 2011). Using passive acoustic detections, Marques et al. (2009) estimated the density of Blainville’s beaked whales at AUTEC was 25.3 or 22.5 animals/1,000 km2, depending on assumptions about false positive detections, with 95% confidence intervals 17.3–36.9 and 15.4–32.9. Using photo-identification data collected at AUTEC from 2005–2019 and an open population mark-recapture modelling approach, Claridge and Dunn (2019) estimated the average annual abundance of 35 whales (95% HPDI, 22 – 54). Notably there have not been any matches of individuals between the South Abaco (n = 130 IDs) and AUTEC (n = 69 IDs) sites (a distance of only 170 km), further supporting the site fidelity and residence of small populations of Blainville’s beaked whales within the IMMA (Claridge et al., in prep).

Adult female sperm whales exhibit strong site fidelity to the Lucayan Archipelago. Photo-identification of sperm whales in the Bahamas has documented between-year re-sightings of adult females and sub-adult males (n = 186 IDs, 36% resighted), and females in particular appear to demonstrate high rates of site fidelity (Claridge et al., 2015; Mullin et al., 2022). Off Abaco Island, where studies began in 1992, over 52% of sperm whales photo-identified were seen in more than one year (n = 103 IDs, 1992-2014), with adult females seen on average 6.5 years (Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, unpubl. data). Satellite telemetry data (n = 27 tags) support this hypothesis with movement tracks showing adult females ranging only within the northern part of the Great Bahama Canyon, while sub-adult males ranged into Tongue of the Ocean, in the southern part of the Canyon and east of the islands (Claridge et al., 2015). Sperm whale density was estimated by Ward et al. (2012) within the Tongue of the Ocean within the northern part of the IMMA, where the average density was 0.16 whales/1,000 km2 (CV 27%; 95% CI 0.095–0.264).

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

Both dwarf (Kogia sima) and pygmy (K. breviceps) sperm whales aggregate in the IMMA, often within 4 km from shore, near the shelf slope, which can drop beyond 3,000 m (MacLeod et al., 2004; Claridge, 2006; Dunphy-Daly et al., 2008; Dunn and Claridge, 2014). Dwarf sperm whale groups are small (median = 2.5, range = 1-8) and tend toward deeper waters (400-1,600 m) in the summer, while in winter groups are larger (median = 4, range = 1-12) and sighting rates were almost six times higher in the shallower slope habitat (400-900 m; Dunphy-Daly et al., 2008). Additional sightings for these species have been documented in the Turks and Caicos Islands farther southeast in the Lucayan Archipelago, including the stranding of a pygmy sperm whale calf in 2021.

Goose-beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris) are regularly sighted and detected acoustically in The Bahamas (Claridge 2006; Claridge et al., 2008; Gillespie et al., 2009; Hazen et al., 2011; Claridge et al., 2015; Joyce et al., 2017). Seven tags were deployed on goose-beaked whales, resulting in 594 location estimates during tag durations up to 92 days (median = 26 days). This species showed a remarkable level of small-scale site fidelity, with whales remaining within 100 km of the tagging site, even for durations of up to 13 weeks. However, photo-identification data did not appear to support long-term site fidelity, although the number of identifications annually was small (89 identifications from The Bahamas from 1993 to 2014). Only 3% of individuals were re-identified in multiple years. Claridge et al. (2012) applied distance sampling methods to line-transect ship-based visual data in the Great Bahama Canyon, and reported abundance and density estimates for Ziphius of 1,380 whales and 49.5 beaked whales/1000 km2 (CV 0.49), respectively.

Melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) aggregate seasonally in the northern Bahamas, where resighting data imply regular use of the area in the spring/summer period. During six years, a total of 410 distinctive individuals were photographed with resights ranging from one to six occasions. Estimates suggest that 558 (95% CRI = 547.00 – 561.00) individuals used the studied area at least once during the study period. Estimates of mean survival were 0.81 (95% CRI = 0.48 – 0.98) and capture probability was 0.36 (95% CRI = 0.33 – 0.41) (Viera, 2017; Viera et al., 2023).

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) with calves are sighted in the south-eastern area of the IMMA in the waters around Inagua and Mayaguana islands in the Bahamas (D. Claridge, Pers. comm, 2024). Further southeast within the easternmost boundary of the IMMA, off the Turks Bank and Caicos Bank, the peak season for humpback whale sightings is between February and March, but data suggests that this species uses the banks continually throughout the breeding season (from January to early April), including 513 individually photo-identified and catalogued with tail flukes and 246 (n = 48%) resightings to other breeding and/or feeding areas (personal communication, Turks and Caicos Islands Whale Project, 2024). There have been resightings from the Turks Bank to all known feeding grounds in the North Atlantic.

During the 2022 season, a total of 67 mother-calf pairs and 13 mother-calf-escort groups (Hart and Bacon, 2022), representing 62% and 12% of all sightings recorded, followed by 20 adult pairs, three competitive groups, four singletons, and one singer. In 2023, 52 mother-calf pairs (45%) and 11 (9%) mother-calf-escort groups were observed, followed by 24 singletons (21%), 22 adult pairs (19%), three singers, and one competitive group of 10 individuals (Turks and Caicos Islands Whale Project unpublished data; Hart and Bacon, 2024).

During both seasons, mother-calf pairs were found in the shallower areas around the cays on the bank, while other adult whales were generally found in deeper water towards the edge of the shelf and are rarely seen amongst mother-calf pairs unless part of a mother-calf-escort group where an adult whale is in direct association with a mother-calf pair (Hart and Bacon, 2022, 2024).

Residency times for mother-calf pairs on the Turks Bank range from 1 day to 29 days (Turks and Caicos Islands Whale Project unpublished data; Hart and Bacon, 2024). Although the majority of North Atlantic humpback whales are seen in the Dominican Republic waters, Turks and Caicos Island waters, such as the Turks Bank, might also be a breeding and nursery area where individuals stay longer periods of time and not just pass through the Turks and Caicos Islands along their migratory route to the high-density areas (TCI unpublished data; Bacon et al., 2023; Hart and Bacon, 2022, 2024).

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

C3a – Whale Seasonal Migratory Route

C3b – Migration / Movement Area

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

The IMMA includes an area with one of the highest known densities of Ziphiids. These include Blainville’s beaked whale, Gervais’ beaked whale (Mesoplodon europaeus) and goose-beaked whale. Claridge et al. (2012) applied distance sampling methods to line-transect ship-based visual data in the Great Bahama Canyon, and reported abundance and density estimates for Ziphiids. Overall estimates of abundance and density of Mesoplodon beaked whales in the Great Bahama Canyon were 1,426 whales and 51.1 beaked whales/1000 km2 (CV 0.40). Abundance and density estimates for Ziphius were 1,380 whales and 49.5 beaked whales/1000 km2 (CV 0.49). Relative density of beaked whales varied by area within the Canyon, with the highest densities found in the southernmost part of Tongue of the Ocean, known as the Cul de Sac. Here the density of Mesoplodon beaked whales was 73.4 whales/1000 km2 (CV 0.61) and Ziphius was 109 whales/1000 km2 (CV 0.65) (Claridge et al., 2012).

The IMMA includes coastal areas inhabited by both the Greater Caribbean and the Florida subspecies of manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus and T. m. latirostris, LeFebvre et al., 2001; Mignucci et al., 2024) making this IMMA unique as a potential zone of interaction for the two subspecies. T. m. latirostris dispersed from Florida have established a local breeding population in islands of the northern Bahamas (Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, unpubl. data; Clark, 2024), but recent sightings in the southern Bahamas (San Salvador, Rum Cay, Mayaguana Islands, Inagua Island) and in Turks and Caicos have been reported (Clark, 2024). These northern records are most probably T. m. latirostris, as of the 15 animals photo-identified, six are known previously from Florida, all of which were sighted in the northern islands. Two females have produced at least nine offspring since immigrating to The Bahamas. There is some limited information to suggest that manatee records from the southern islands document the occurrence of T. m. manatus. The only specimen known from the southern region is the cranium collected in the 1980s from a dead stranded manatee on Great Inagua Island which was later examined by Daryl Domning at the Bahamas National Trust office in Nassau and determined to be T. m. manatus (Lynn Gape, BNT, pers.comm). Given that the proximity of the southern Bahamas to Cuba and Hispaniola is similar to that from the northern islands to Florida (approx. 80 km), and that the Antillean Current runs north towards the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos as opposed to the Gulf Stream flowing away from The Bahamas, it is likely that manatees found in the southern part of the Lucayan Archipelago are T. m. manatus.

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

The IMMA encompasses a vast range of habitats which allow this area to sustain a wide variety of both resident and seasonally present marine mammals. These habitats include tidal creeks, patch and fringing reefs, barrier reefs, extensive seagrass beds, sea submarine canyons, including the Great Bahama Canyon which is the world’s largest submarine canyon. Although the surface waters of the region are generally described as oligotrophic, these deep-water environments are more productive and thus support a high diversity of odontocete species found in the area.

In addition to the 17 species known to inhabit the archipelago and listed in the criteria above, an additional nine marine mammal species have been recorded (Balcomb 1981; Claridge and Balcomb 1993; MacLeod et al., 2004; Claridge et al., 2102, 2015; Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, unpublished data; Hart and Bacon, 2022, 2024; Turks and Caicos Islands, unpublished data). These include minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni), fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus), short-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata), false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens), Clymene dolphins (Stenella clymene), striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba), and Gray’s spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris longirostris).

For The Bahamas region, the majority of sighting data were collected during non-random shore-based small-vessel surveys and limited primarily to the northern part of the archipelago. However, the proximity of deep-water environments to shore allowed surveys to cover habitats ranging from mangrove lagoons to deep sea canyons. From 2007-2013, ship-based platforms were utilised to conduct line transect and non-random surveys of the Great Bahama Canyon, transerving the entirety of this canyon system. With more than 7200 records when species identification is confirmed, the predominant species are common bottlenose dolphin (52%), Blainville’s beaked whale (10%), West Indian manatee (9%), dwarf sperm whale (8%), sperm whale (7%), and Atlantic spotted dolphin (4%) (Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, unpublished data).

During the 2022 to 2024 seasons, data were collected by the Turks and Caicos Islands Whale Project under the Department of Environment and Coastal Resources Scientific Research Permit numbers 2021-12-29-26, 2022-12-22-44, and 2024-03-04-09, primarily on private whale watching excursions conducted on the Turks Bank by Deep Blue Charters. Off the Turks and Caicos Islands, the species encountered during these surveys consisted of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), followed by bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), and Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis).

Supporting Information

Angel, M. 2011. The pelagic ocean assemblages of the Sargasso Sea around Bermuda. Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series, No. 1, 25 pp.

Beaudette, A., Allen, J., Bort, J., Stevenson, A., Stevick, P. and Stone, G. 2009. Poster presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 18th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Quebec City, Canada, 12-16 October 2009.

Coates, K.A., Fourqurean, J.W., Kenworthy, W.J., Logan, A., Manuel, S.A. and Smith, S.R. 2013. Introduction to Bermuda: geology, oceanography and climate. In Coral reefs of the United Kingdom overseas territories. Pp.115-133. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Fahlman, A., Tyson Moore, R.B., Stone, R., Sweeney, J., Trainor, R.F., Barleycorn, A.A., McHugh, K., Allen, J.B. and Wells, R.S. 2023. Deep diving by offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.). Marine Mammal Science 39:1251-1266.

Fawcett, S. E., Lomas, M.W., Ward, B.B. and Sigman, D.M. 2014. The counterintuitive effect of summer-to-fall mixed layer deepening on eukaryotic new production in the Sargasso Sea. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 28:86–102.

Grove, T., King, R., Henry, L.-A. and Stevenson, A. 2022. Modelled annual abundance of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae around Bermuda, 2011-2020. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.945442.

Grove, T., King, R., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2023. A decade of humpback whale abundance estimates at Bermuda, an oceanic migratory stopover. Frontiers in Marine Science 9:971801.

Ham, J.R., Lilley, M.K. and Manitzas Hill, H.M. 2023. Non-conceptive sexual behavior in cetaceans: comparison of form and function. In: Würsig, B., and Orbach, D.H. (eds.) Sex in Cetaceans: Morphology, Behavior, and the Evolution of Sexual Strategies, pp.129-152. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Hay, C., Henry, L.-A., Roberts, J.M. and Stevenson, A. 2024. Spatial layers examining whether a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area can be justified in Bermuda to aid in cetacean conservation. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.961168.

Katona, S.K. and Beard, J.A. 1990. Population size, migrations and feeding aggregations of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 12, pp.295-306.

Kettemer, L.E. 2023. Migration ecology of North Atlantic humpback whales: mapping movements throughout the annual cycle. PhD thesis, Arctic University of Norway.

Klatsky, L.J., Wells, R.S. and Sweeney, J.C. 2007. Offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Movement and dive behavior near the Bermuda Pedestal. Journal of Mammalogy 88:59-66.

Narganes Homfeldt, T., Risch, D., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2022a. Seasonal and diel patterns in singing activity of humpback whales migrating through Bermuda. Frontiers in Marine Science 9:941793.

Narganes Homfeldt, T., Risch, D., Stevenson, A. and Henry, L.-A. 2022b. Spectrograms of singing humpback whales migrating through Bermuda. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.946517.

Payne, K. and Payne, R. 1985. Large scale changes over 19 years in songs of humpback whales in Bermuda. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 68:89-114.

Stevenson, A. 2011. Humpback whale research project, Bermuda. Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series, No 11, 11pp. ISBN 978-0-9892577-3-2.

Stevenson, A. 2019. The Secret Lives of the Humpbacks. Directed by Andrew Stevenson, Bermuda. https://vimeo.com/354733042.

Stevenson, A. Forthcoming. Observation dates of Cuvier’s beaked whales and bottlenose dolphins around Bermuda. Report to the Sargasso Sea Commission.

Stevenson, A., Rigaux, C., Stringer, C., van de Weg, R. and Clee, J. 2017. The secret mid-ocean lives of humpback whales: pelagic social behaviour of North Atlantic humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) evidenced by 1500+ fluke IDs plus underwater and aerial footage. Poster presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Halifax, Canada, 23-27 October, 2017.

Stevenson, A. and Werth, A. 2024. Humpback whales inflate pleated oral pouch to scratch an itch and detach parasites. Marine Mammal Science e13127.

Stone, G.S., Katona, S.K. and Tucker, E.B. 1987. History, migration and present status of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae at Bermuda. Biological Conservation 42:133-145.

Wells, R.S., Fahlman, A., Moore, M., Jensen, F., Sweeney, J., Stone, R., Barleycorn, A., Trainor, R., Allen, J., McHugh, K., Brenneman, S., Allen, A., Klatsky, L. and Douglas, D. 2017. Bottlenose dolphins in the Sargasso Sea – Ranging, diving, and deep foraging. Oral presentation at The Society for Marine Mammalogy’s 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Halifax, Canada, 23-27 October, 2017.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Lucayan Archipelago IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile and/or geojson) for the Lucayan Archipelago IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: