Size in Square Kilometres

376

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Greater Caribbean Manatee – Trichechus manatus manatus

Criterion A; B (1)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Summary

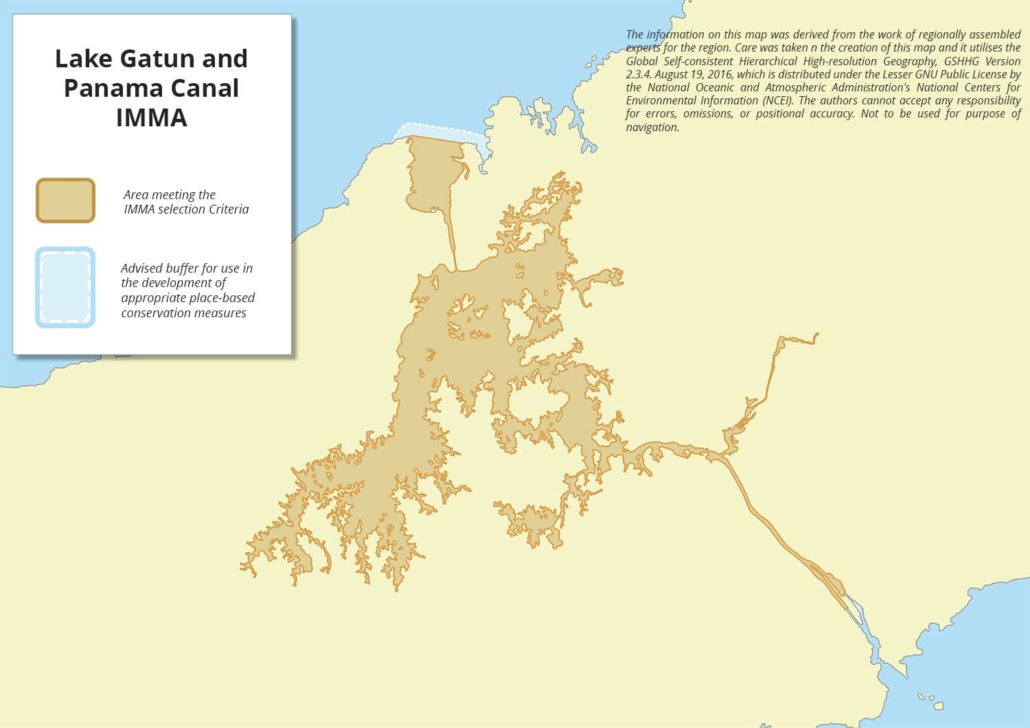

The Lake Gatun and Panama Canal IMMA includes the Panama Canal, Lake Gatun, and surrounding wetlands. The artificial lake, created for the operations of the Panama Canal, is uniquely situated 26 m above sea level and provides important habitat to a population of Endangered Antillean/Greater Caribbean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus). The secluded population in Gatun Lake and the Panama Canal has grown from 10 animals that were translocated from Peru and the Bocas Del Toro area in the north of Panama in 1964, and now composes a minimum of 16 individuals. Connectivity for this population segment, removed from its original natural habitat, is limited by man-made canal locks operations. Population viability is currently being assessed.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

This IMMA encompasses the habitat of the Caribbean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus), recognized as the Antillean manatee by the Society for Marine Mammalogy’s Committee on Taxonomy. The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) as a species is globally assessed Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (Deutsch and Morales-Vela, 2024), but the Caribbean sub-species is considered Endangered (Morales-Vela et al. 2024). At local levels, the Caribbean manatee is also listed and protected as Endangered by the Ministry of Environment of Panama (Resolution N0. DM-0657, 2016). Self-Sullivan and Mignucci-Giannoni (2012) reported population estimates for Panama and Costa Rica at 100 individuals each, with minimum counts of 10 and 30, respectively, suggesting a critical status.

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

In 1964 ten individual manatees – one male Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis) and nine Greater Caribbean manatees from the Changuinola region in the north of Panama – were translocated into Lake Gatun, an artificial lake created during the construction of the Panama Canal (Nillipour, 2022; Muschett and Vianna, 2015). The original motivation for bringing in these manatees was to control growth of the water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes), which was thought to create breeding habitat for mosquitoes (MacLaren, 1967, Nillipour, 2022; Muschett and Morales 2020).

A study conducted in 2007 using aerial, small boat and interview surveys estimated the population to contain a minimum of 16 individuals, including newborn calves and juveniles, and noted that vegetation in the lake included many species known to feature in manatee diets: Eichhornia crassipes, Pistia stratiotes, Pontederia rotundifolia and Hydrilla verticillata, (Muschett and Vianna, 2015). This minimum estimate is thought to be a significant underestimate, given the frequency of reports from interviewed villagers, and the turbidity of the water that hindered boat- or aerial based observations (Muschett and Morales 2020).

A more recent population viability modelling exercise determined that the survival of the original population may only have been possible with the immigration by individuals that entered the Canal from the Caribbean through the Canal locks (Muschett and Morales 2020), and there is even speculation, based on an observation of an Antillean manatee on the Pacific side of the Panama canal, that at least one animal from the Lake Gatun population may have crossed over into the Pacific (Guzman and Real, 2022). However, the authors indicate that such immigration and emigration is unlikely to occur regularly given the complexity of the lock systems and the high volumes of vessel traffic using the system, and that for most practical purposes the population should be considered discrete and isolated (Muschett and Morales, 2020; Guzman and Real, 2022).

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

C3a – Whale Seasonal Migratory Route

C3b – Migration / Movement Area

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

Supporting Information

Castelblanco-Martínez, D.N., Nourisson, C., Quintana-Rizzo, E., Padilla-Saldivar, J. and Schmitter-Soto, J.J., 2012. Potential effects of human pressure and habitat fragmentation on population viability of the Antillean manatee Trichechus manatus manatus: a predictive model. Endangered Species Research, 18(2), pp.129-145.

Deutsch, C.J. & Morales-Vela, B. 2024. Trichechus manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22103A43792740. Accessed on 15 November 2024.

Guzman H.M. & Real, C.K. 2023. ‘Have Antillean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus) entered the Eastern Pacific Ocean?’. Marine Mammals Science. 39:274-280.

Jiménez, I., 2005. Development of predictive models to explain the distribution of the West Indian manatee Trichechus manatus in tropical watercourses. Biological Conservation, 125(4), pp.491-503.

Lépiz, A. G. 2010. Plantas emergentes y flotantes en la dieta del manatí (Familia: Trichechidae: Trichechus manatus) en el Caribe de Costa Rica. Journal of Marine and Coastal Sciences, 2, 119-134.

Marsh, H., O’Shea, T.J., Reynolds, J.E., 2011. Ecology and conservation of the Sirenia: dugongs and manatees (No. 18). Cambridge University Press.

Mou Sue, L.L., Chen, D. H., Bonde, R.K. & O’Shea, T.J. 1990. ‘Distribution and status of manatees (Trichechus manatus) in Panama’. Marine Mammals Science 6:234–241

Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A., D. González-Socoloske, A. Álvarez-Alemán, J. Aquino, D. Caicedo-Herrera, D.N. Castelblanco-Martínez, D. Claridge, M.F. Corona-Figueroa, A.O. Debrot, B. de Thoisy, C. Espinoza-Marín, J.A. Galves, E. García-Alfonso, H.M. Guzmán, J.A. Khan, J.J. Kiszka, F. de Oliveira Luna, M. Marmontel, L.D. Olivera-Gómez, C. O’Sullivan, J.A. Powell, E. Pugibet-Bobea, I. Roopsind, & C.J. Silva. 2024. ‘What’s in a name? Standardization of vernacular names for Trichechus manatus. Caribbean Naturalist’ (in press).

Muschett, G, Morales, N. S. 2020. Using ecological modelling to assess the long-term survival of the West-Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus) in the Panama Canal. Water. 12: 1275.

Muschett, G. & Vianna, J.A. 2015. Distribution and abundance of the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) in the Panama Canal. bioRxiv 2015, 26724.

Nillipour, L. 2022 Have Antillean manatees crossed the Panama Canal? Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Available online: https://stri.si.edu/story/manatee-lagoon

Self-Sullivan, C., and A. Mignucci-Giannoni. 2012. West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus) in the wider Caribbean region. Pages 36–46 in E. M. Hines, J. E. Reynolds, L. V. Aragones, A. A. Mignucci-Giannoni, and M. Marmontel, editors. Sirenian conservation, issues and strategies in developing countries. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, USA.

Schad, R.C., Montgomery, G. & Chancellor, D. 1981. La distribución y frecuencia del manatí en el lago Gatún y el Canal de Panamá’. ConCiencia. 8, 1–4.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Lake Gatun and Panama Canal IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile and/or geojson) for the Lake Gatun and Panama Canal IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: