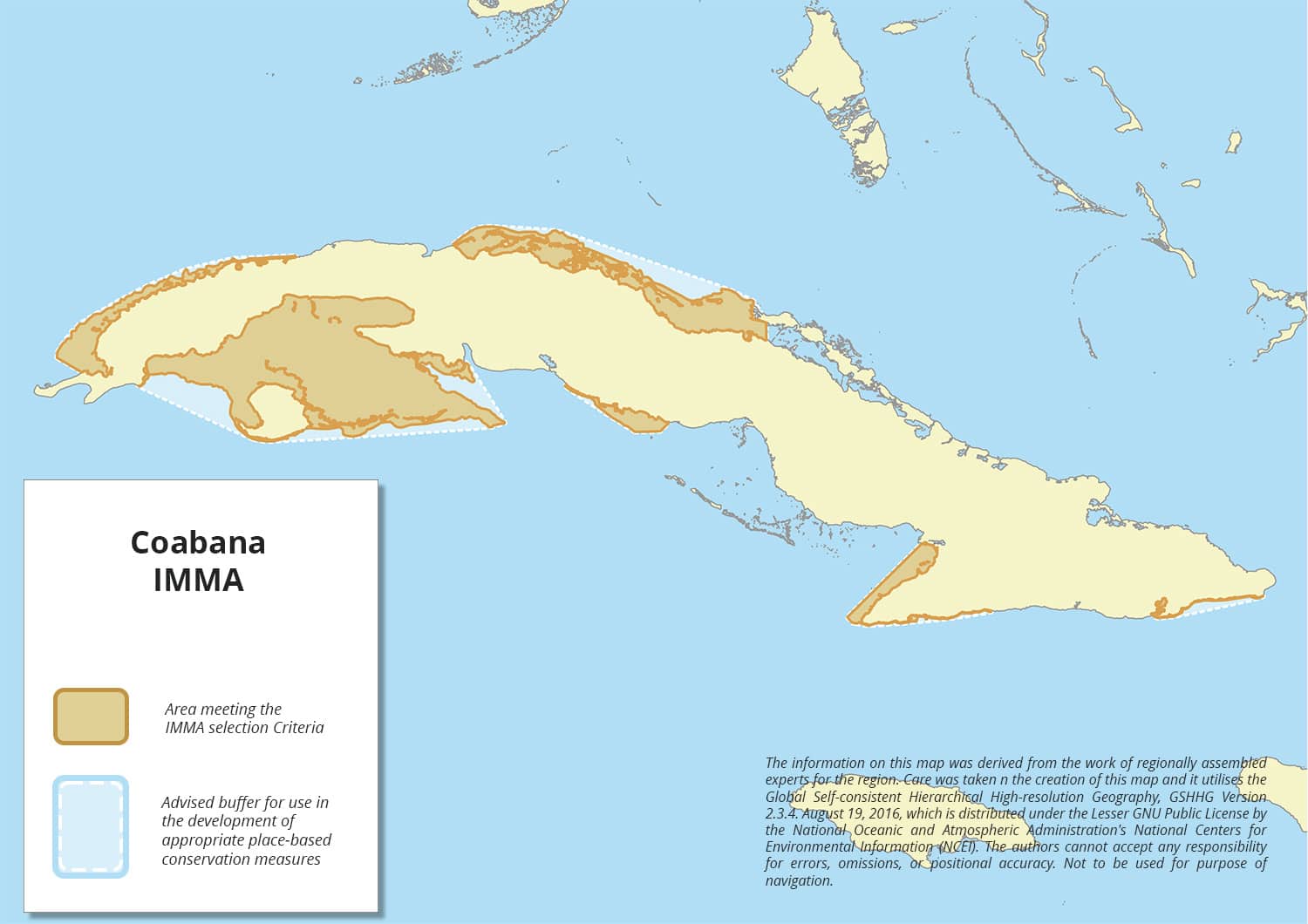

Coabana IMMA

Size in Square Kilometres

33 078 km2

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Greater Caribbean Manatee – Trichechus manatus manatus

Criterion A; Criterion B (2); Criterion C (1, 2)

Download fact sheet

Summary

The Coabana Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) encompasses bays and coastal areas around the Cuban archipelago. About 50% of the Cuban shelf is covered by seagrass meadows. Together with the island’s extensive system of over 600 rivers, the IMMA provides important feeding, breeding, and aggregating habitat for Endangered Greater Caribbean/Antillean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus), which are found in multiple hotspots around the islands inland and coastal waters.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A: Species or Population Vulnerability

The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) has a broad distribution throughout the West Atlantic, Caribbean, and coastal Central and South America (Lefebvre et al. 2001). The species is assessed as “Vulnerable” (Deutsch and Morales-Vela, 2024) while the subspecies, the Greater Caribbean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) is classified as “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Morales-Vela et al. 2024).

Criterion B: Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B2: Aggregations

Greater Caribbean manatees once occupied much of Cuba’s coastal habitat, with significant concentrations near numerous river mouths and associated to seagrass beds (Cuni 1918; Lefebvre et al. 2001; Alvarez-Aleman et al 2018a). The species can be found island-wide, but based on results obtained through fisheries interviews, aerial surveys, telemetry and boat surveys, higher levels of occurrences are detected in at least 20 areas across the archipelago. Aerial surveys with flight hours ranging from 4.8 to 9.5 hours conducted between 1985 and 1992 in southern Matanzas and Sancti Spiritus provinces recorded between 20 and 59 manatees (Alvarez-Aleman et al 2018a). Moreover, boat-based surveys in Ciénaga de Lanier, southwest Cuba, from 2007 to 2013, detected manatees on 47% of survey days and 96% of trips, with 133 manatees observed in 93 sightings at a rate of 0.2 sightings per hour. The study concluded that the Ciénaga de Lanier Wildlife Refuge offers essential resources for manatees, such as springs, mangrove creeks, fresh water, feeding areas, and thermal refuges. Other Boat surveys in Desembarco del Granma, Granma Province, and off Cayo Levisa, Pinar del Río Province, involved over 800 hours and 8-18 hours of effort, respectively. Encounter rates during these surveys ranged from 0.05 to 1.8 manatee encounters per hour.

Preliminary studies of manatee habitat use in Cuba, conducted between 2012 and 2015 in Guantanamo Bay and Isla de la Juventud, tracked the movement of eight and three GPS-tagged manatees, respectively. In Guantanamo, manatees remained within 50 km of the coastline, moving between the bay and Guantánamo River for fresh water, while on Isla de la Juventud, a female and mother-calf pair stayed within 25 km along the western coastline, and a male travelled up to 50 km, including areas near San Felipe Keys and Punta Frances. While these survey methods have indicated that manatee distribution may be patchy and concentrated in specific ‘hotspots’ across the archipelago (Alvarez-Aleman et al. 2018a), genetic studies indicate a non-panmictic population, with regular gene flow occurring across the western portion of the archipelago and low connectivity between the south-eastern Guantanamo Bay region and the western portion (Alvarez-Aleman, 2019).

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1: Reproductive Areas

The presence of calves and mother-calf resting behaviour have been observed in Siguanea Gulf, Isla de la Juventud which indicated suitable reproductive habitat that provides protection and resting areas to mothers and new-born calves (Alvarez-Aleman et al. 2016). In this portion of the IMMA, mother/calf pairs were observed during seven of the 26 survey trips, but during the last 3 years of surveys mother/calf pairs were observed during 63% of the trips (Alvarez-Aleman et al. 2016). Additionally, mother-calf pairs have opportunistically been reported across the Cuban archipelago and through stranding reports (Alvarez-Aleman et al. 2018a). Furthermore, opportunistic observations of mating herds have been recorded from the Zapata Peninsula.

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

About 50% of the Cuban shelf is covered by seagrass meadows (Martinez-Daranas et al. 2018). The abundance of Cuban seagrasses varies across different areas of the shelf, but Thalassia testudinum is the most common species. Other species, usually with lower biomass, include Syringodium filiforme, Halodule wrightii, Halophila decipiens, Halophila engelmannii, Halophila ovalis, Halophila baillonis, and Ruppia maritima (Martinez-Daranas et al. 2018).

Cuba’s extensive coastal habitats with seagrass beds and over 600 rivers could, in theory, support a considerable number of the Greater Caribbean manatees (Alcolado 2006; Baisre and Arboleya 2006). Seagrass species that are frequently observed in the digestive tract contents of manatees, or in association with observations of the animals include Thalassia, Syringodium, Halophila, and Halodule. In some areas of the archipelago, Halodule is preferred to other marine seagrass species (Alvarez-Aleman 2010, Navarro et al. 2014). Alvarez-Aleman et al. (2016) observed feeding behaviour in 10 % of the sightings recorded in Isla de la Juventud, in areas dominated by Thalassia testudinum, with some patches of Halodule wrightii.

Supporting Information

Alcolado PM (2006) Diversidad ecológica. Diversidad, utilidad y estado de conservación de los biotopos marinos. In: Claro R (ed) La Biodiversidad Marina de Cuba. Instituto de Oceanología Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente, La Habana, pp 39

Alvarez-Alemán A, Powell JA, Beck C (2010) First report of a Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) in Cuba. Aquat Mamm 36:148–153.

Alvarez-Alemán A. 2010. Estado actual del manatí (Trichechus manatus) en la Ensenada de la Siguanea: consideraciones para su conservación. Master’s thesis in Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Thesis, University of Havana, Cuba.

Alvarez-Alemán A, Angulo-Valdés J, Powell J, García E, Taylor CK (2016) Antillean manatee occurrence in a marine protected area, Isla de la Juventud, Cuba. Oryx. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315001143

Alvarez-Alemán A, García E, Forneiro Martin-Viana Y, Hernández González Z, Escalona-Domenech R et al (2018a) Status and conservation of manatees in Cuba: historical observations and recent insights. Bull Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2016.1132

Alvarez-Alemán A, Austin JD, Jacoby CA, Frazer TK (2018b) Cuban connection: regional role for Florida’s manatees. Front Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00294

Alvarez-Aleman A (2019) Population Genetics and Conservation of the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) in Cuba. A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 216 pp.

Alvarez-Alemán A, Garcia-Alfonso E, Powell JA, Jacoby CA, Austin JD, Frazer TK (2021) Causes of mortality for endangered Antillean manatees in Cuba. Front Mater Sci 8:646021

Alvarez-Aleman, A., Gonzalez-Socoloske, D., Garcia-Dulzaides, B., Rodriguez-Viera, L. (2021) First report of pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata) in Cuba. Aquatic Mammals 47(1), 71-75, DOI

Alvarez-Aleman et al 2022. The first assessment of the genetic diversity and structure of the endangered West Indian manatee in Cuba. Genetica. 150: 327-341.

Areces AJ. (2002) Ecoregionalización y clasificación de hábitats marinos en la plataforma cubana: resultados. Havana: Instituto oceanología, WWF-Canada, Environmental Defense, Centro Nacional de Áreas Protegidas.

Baisre JA, Arboleya Z (2006) Going against the flow: effects of river damming in Cuban fisheries. Fish Res 81:283–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FISHRES.2006.04.019

Blanco, M. (2008) Varamientos de Ballenas Edentadas en costas y aguas cubana. Rev Inv Mar. 29 (1): 81-85.

Blanco, M. (2011) Ballenas y delfines. In Borroto-Páez, R. and Mancina, C.A. (Eds) Mamíferos en Cuba (pp. 186-201). UPC Print, Vasa, Finlandia

Blanco, M. (2013).Varamientos y avistamientos de Physeter macrocephalus (Mammalia: Physeteridae) en las costas y aguas de la plataforma cubana. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Biológicas, 2 (1): 4pp

Castelblanco-Martínez, DN., Alvarez-Alemán, A., Torres, R., Teague, A.L., Barton, SL., Rood, KA., Ramos, EA., & Mignucci-Giannoni, A.A. (2021) First documentation of long-distance travel by a Florida manatee to the Mexican Caribbean, Ethology Ecology & Evolution, DOI: 10.1080/03949370.2021.1967457

Cuni LA (1918) Contribución al estudio de los mamíferos acuáticos observados en las costas de Cuba. Memorias de la Sociedad Cubana de Historia Natural. Felipe Poey 3:83–126.

Deeks, E., Kratina, P., Normande, I., Cerqueira, A. S., & Dawson, T. (2024). Proximity to freshwater and seagrass availability mediate the impacts of climate change on the distribution of the West Indian manatee. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 19(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00321

Deutsch, C.J. & Morales-Vela, B. 2024. Trichechus manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22103A43792740. Accessed on 03 November 2024. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T22103A9356917.en. Accessed on 27 August 2024.

Frankham R (1995) Conservation genetics. Annu Rev Genet 29:305–27.

Frankham R, Corey JA, Bradshaw C, Brook BW (2014) Genetics in conservation management: Revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. Biol Conserv 170: 56–63

Funk WC, McKay JK, Hohenlohe PA, Allendorf FW (2012) Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends Ecol Evol 27(9):489–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.012

Garcia-Machado E, Ulmo-Diaz. G, Castellanos-Gell J, Casane D. 2028. Patterns of population Connectivity in Marine Organisms of Cuba. Bull Mar Sci. 94(2):193–211. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2016.1117

Garrison LP, Soldevilla MS, Martinez A, Mullin KD (2024) A density surface model describing the habitat of the Critically Endangered Rice’s whale Balaenoptera ricei in the Gulf of Mexico. Endang Species Res 54:41-58. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01324

Hernandez-Albernas J and Helguera Y (2022) First confirmed record of a fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in the north coast of Cuba. Revista de Investigaciones Marinas. 42(1): 145-150 pp.

Hunter ME, Mignucci-Giannoni AA, King TL, Tucker KP, Bonde RK (2012) Comprehensive genetic investigation recognizes evolutionary divergence in the Florida (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and

Puerto Rico (T.m. manatus) manatee populations and subtle substructure in Puerto Rico. Conserv Genet 13:1623–1635

Lefebvre LW, Marmontel M, Reid JP, Rathbun GB, Domning DP (2001) Status and biogeography of the West Indian manatee. In: Woods CA, Sergile FE (ed) Biogeography of the West Indies, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, pp 425–474

Martínez-Daranas B, Cano M, Clero L. 2009b. Los pastos marinos de Cuba: estado de conservación y manejo. Ser Oceanol. 5:24–44. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259791374_Los_pastos_marinos_de_Cuba_estado_de_conservacion_y_manejo

Martínez-Daranas B, Suárez AM (2018) An overview of Cuban seasgrasses. Bull Mar Sci 94:269–282.

Morales-Vela, B., Quintana-Rizzo, E. & Mignucci-Giannoni, A. 2024. Trichechus manatus ssp. manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22105A43793924. Accessed on 03 November 2024.

Navarro ZM, Alvarez-Aleman A, Castelblanco-Martinez N (2014) Componentes de la dieta en tres individuos de manati en Cuba. Revista de Investigaciones Marinas. 34(2): 1-11.

Nuney L (1992) The influence of mating system and overlapping generations on effective population size. Int J Org Evolution https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02158.x

Nunney L, Elam DR (1994) Estimating the effective population size of conserved populations. Conserv Biol 8:175–184

Self-Sullivan C, Mignucci-Giannoni A (2008). Trichechus manatus ssp. manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T22105A9359161.

Waples RS, Do C (2008) LdNe: a program for estimating effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Mol Ecol Resour 8:753–756

Waples RS, Do C (2010) Linkage disequilibrium estimates of contemporary Ne using highly variable genetic markers: a largely untapped resource for applied conservation and evolution. Evol Appl 3(3):244–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4571.2009.00104.x

Willi Y, Van Buskirk J, Hoffman AA (2006) Limits to the adaptive potential of small populations. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37: 433-458

Whitt, A.D., Jefferson, T.A., Blanco, M., Fertl, D., and Rees, D. (2011) A review of marine mammal records of Cuba. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 9(2): 65-122.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Coabana IMMA using the Fact Sheet button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile) for the Coabana IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: