Caspian seal moulting and haul-out areas IMMA

Size in Square Kilometres

35 351 km2

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Caspian Seal – Pusa caspica

Criterion A, B2, D1

Marine Mammal Diversity

Pusa caspica

Download fact sheet

Summary

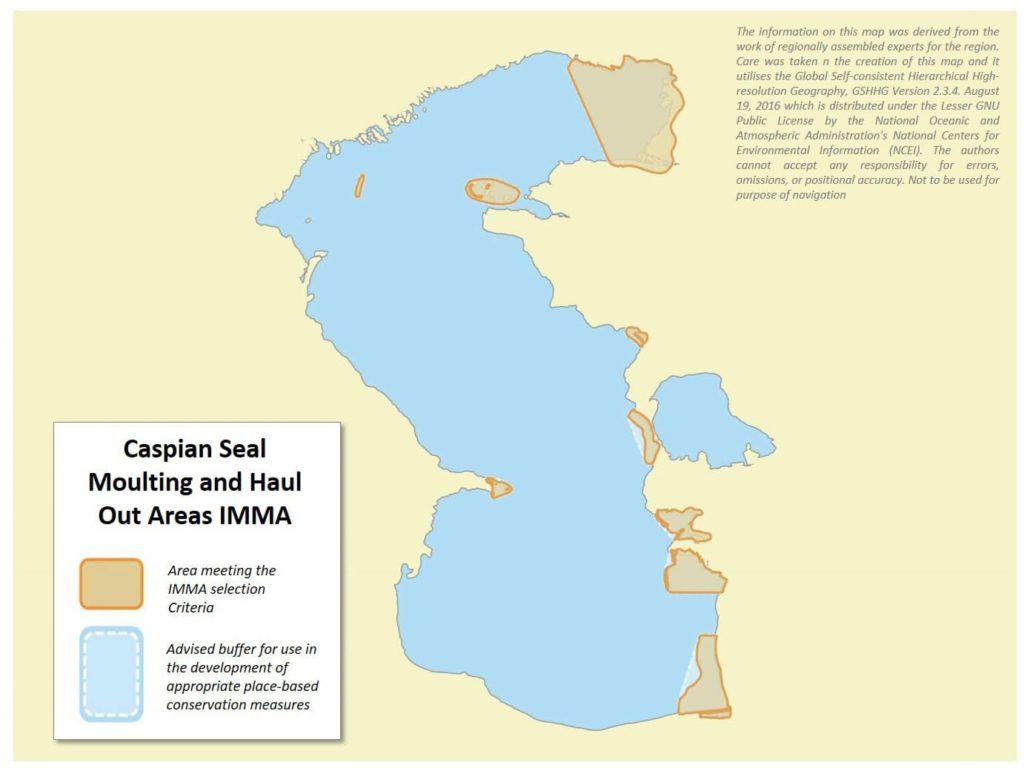

Coastal areas used by Caspian seals for moulting in the spring and haul-out during the summer and autumn migrations in the past 30 years, are listed here. Two areas in the north Caspian, the region between Komsomlolet’s Bay and Prorva in the northeast, and Maly Zhemchuzhniy Island in the northwest, support thousands of seals, mainly breeding adults, during the spring moult immediately following the ice melt in March. Other sites in current use typically host 10s to 100s of seals seasonally. The Absheron Peninsula in the west, and islands in the Ogurchinsky (Ogurjali) area are reported to have supported tens of thousands of seals historically, falling to a few hundreds in the early 21st century, and to a few tens in the most recent years. The only former terrestrial pupping site documented was on Ogurchinsky Island in the 1980s. Eight pups were recorded there in 2002, but none since then.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

The Caspian seal is listed as Endangered by IUCN (Goodman & Dmitrieva 2016), and in the Red lists of all 5 littoral states (Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan). Since it is landlocked within the Caspian Sea it has no possibility of migration to alternate areas, and therefore is entirely dependent on the Caspian environment. The IMMA encompasses the primary locations used by Caspian seals for moulting and hauling out.

The Caspian seal is an amphibious mammal, which requires suitable solid substrate (“haul-out sites”), clear of the water, for resting. All Caspian seals more than one year old undergo an annual spring moult, lasting 4–6 weeks during late March and April. During the moult they spend most of their time hauled-out at suitable location where they can stay dry for as long as possible. This prolonged hauling out enables the seals to minimise the energy cost of the moult by maintaining a high skin surface temperature which optimises the growth of new hair (Paterson et al. 2012).

Criterion B: Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B2: Aggregations

The sites incorporated into this IMMA form a discontinuous network of locations known to be in current use for haul-out and/or moulting; or locations where satellite telemetry tracks show seals still utilising waters around sites where aggregations are now rare or not observed, but are known to have occurred historically. Human disturbance appears to be the main cause of recent site abandonments, but sea level changes are also a factor in some cases. The sites listed here which have experienced declines in haul-out have potential for restoration if anthropogenic disturbance can be controlled. Outside of these areas through the rest of the Caspian, either the habitat features preferred by seals for hauling out are not present, or the habitats are currently too degraded to support seals.

Supporting evidence is derived from aerial surveys, boat/shore based observations and monitoring, and satellite telemetry studies (Wilson and Goodman 2012; Dmitrieva et al. 2016). However, few locations have frequent, systematic monitoring. In each case IMMA boundaries encompass a terrestrial haul-out site or group of sites within a continuous area, plus the adjacent waters that allow access by seals. Some locations overlap with previously designated EBSAs (Convention on Biological Diversity 2017), in which case the EBSA boundary was adopted. The westward boundary of the northeast Caspian polygon was extended to allow for anticipated sea level declines making sites in current use inaccessible, and the adoption of newly emergent islands.

The sizes of haul-out groups, and frequency and seasonality of use vary considerably. Some haul out sites in the north Caspian (e.g. the area between Komsomolets Bay and Prorva, and Maly Zhemchuzhniy) attract thousands of moulting seals, but most currently host 10s to hundreds of seals seasonally. Haul-out sites for which there are records are listed here according to geography, starting with sites in the northeast Caspian (Kazakhstan) and proceeding clockwise around the Caspian coast. A detailed description for each location is given in Annex 1.

Kazakhstan

- South West Island (Ural delta, 46.74°N 51.64°E).

- Northeast Caspian including, Shalygas (sandy islands, approximately 46.42°N 52.46°E), Prorva approximately (46.06°N 52.76°E) and Komsomolets Bay (approximately 40.39°N 52.63°E).

- Kulali archipelago including Tuylenii islands and Maly Rybachi island (44.76°N 50.37°E).

- Kenderli Bay (42.68°N, 52.63°E).

Turkmenistan

- Kara-Ada island (Bekdash) (41.52°N, 52.70°E).

- Tuylenii islands (41.05°N 52.86°E).

- Bolshoi Osushnoy Island (39.67°N 53.11°E).

- Ogurjali (Ogurchinsky) Island (38.76°N 53.07°E).

- Essenguly (between approximately 37.9°N 53.79°E and 36.85°N 53.46°E)

Islamic Republic of Iran

There are no documented haul-out sites for Caspian seals on the Iranian coast at the present time.

Azerbaijan

- Absheron Archipelago (between approximately 40.39°N 50.36°E and 40.28°N 50.54°E).

- Shakhova Kosa (Shahdili) (40.19°N 50.37°E).

Russian Federation

- Maly Zhemchuzhniy (Small Pearl Island; 44.97°N, 48.28°E).

Criterion D: Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1: Distinctiveness

The D1 criterion of Distinctiveness could be applied to the site of Ogurchinsky (Orgujali) and Mikhailov Islands in Turkmenistan. Krylov (1990) recorded pupping on the sand spit on the southern tip of Ogurchinsky Island, with approximately 50 breeding females (1983–84), but stated that the numbers appeared to be increasing at that time. The last record of pupping was of eight pups born on the spit in January 2002, four of which were photographed alive on the spit (P. Erokhin, unpublished data; Fig. A10). Counts on Ogurchinsky in recent years (2016–20) have not included January, and two counts in February 2019 did not mention pups.

This site on the Ogurchinsky (Orgujali) spit is the only known site away from the ice sheet where pups are known to have been born regularly, at least during the latter part of the 20th century, and potentially reflects a rare ecologically distinct behaviour. The Caspian seal – similar to the closely-related grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) – may be able to breed successfully at onshore sites, with pups surviving to weaning. Such ability could be important in the future if the ice sheet no longer forms in the winter due to climate heating.

Supporting Information

Allchin, C., Barrett, T., Duck, C., Eybatov, T., Forsyth, M., Kennedy, S. and Wilson, S. 1997. Surveys of Caspian seals in the Apsheron Peninsula region and residue and pathology analyses of dead seal tissues. pp. 101-108 in H. Dumont, S. Wilson, and B. Wazniewicz (eds.), Proceedings from the first Bio-network workshop, Bordeaux, November 1997. Caspian Environment Program, World Bank.

Berdiyev, B. and Zakaryaeva, S. 2010. Report on conservation of the Caspian seal in the Turkmen sector of the Caspian Sea and the sites proposed for regular monitoring. Turkmenistan Country Report to CASPECO project Component 1, 2011.

Convention on Biological Diversity 2017. Report Of The Regional Workshop To Facilitate The Description Of Ecologically Or Biologically Significant Marine Areas In The Black Sea And Caspian Sea. https://www.cbd.int/meetings/EBSAWS-2017-01.

Dmitrieva, L., Jüssi, M., Jüssi, I., Kasymbekov, Y., Verevkin, M., Baimukanov, M., Wilson, S. and Goodman, S.J. 2016. Individual variation in seasonal movements and foraging strategies of a land-locked, ice-breeding pinniped. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 554: 241–256.

Eybatov, T.M. 1997. Caspian seal mortality in Azerbaijan. In. Caspian Environment Program. Proc. 1st Bio-Network workshop, Bordeaux, November 1997, eds. H. Dumont, S. Wilson and B Wazniewicz. Pp. 95–100.

Eybatov, T., Asadi, H., Erokhin, P., Kuiken, T., Jepson, P., Deaville, R., and Wilson, S. 2002. Caspian seal (Phoca caspica) mortality. ECOTOX study Final Report, Appendix A. Worl Bank.

Eybatov, T.M. and Rustamova, K.M. 2010. National report on the status of the Caspian seal population in the Azerbaijani waters of the Caspian Sea. Report prepared for CASPECO project Component 1, 2011.

Forsyth, M.A., Kennedy, S., Wilson, S., Eybatov, T. and Barrett, T. 1998. Canine distemper in a Caspian seal. Veterinary Record 143: 662–664.

Goodman, S. & Dmitrieva, L. 2016. Pusa caspica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41669A45230700. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305.

Kuznetsov, V.V. 2010. Creating a network of Caspian seal special protected areas (SSPAs) in the Russian Federation. National Report.

Paterson, W., Sparling, C.E., Thompson, D., Pomeroy, P.P., Currie, J.I. and McCafferty, D.J. 2012. Seals like it hot: changes in surface temperature of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) from late pregnancy to moult. Journal of Thermal Biology, 37: 454–461.

Prange M, Wilke T and Wesselingh FP. 2020. The other side of sea level change. Communications Earth and Environment 1:69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00075-6

Vereschagin, N.K. and Gromov, I.M. 1952. Contribution to the history of the vertebrates of the area of the lower course of the River Ural. Trudy Zoologicheskogo Inta Akad. Nauk S.S.S.R., IX: 1226-1269. (Cited by Chapskii 1955).

Wilson, S.C. and Goodman, S.J. 2012. Caspeco Project Component 1. Creation of Special Protected Areas for the Caspian seal. In CASPECO project Component 1. Seal Special Protected Area scoping and inception plan. Final Report, May 2012. University of Leeds. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Caspeco+project+documents Downloaded on 16/02/20

Wilson, S.C., Eybatov, T.M., Amano, M., Jepson, P.D. and Goodman, S.J. 2014. The role of canine distemper virus and persistent organic pollutants in mortality patterns of Caspian seals (Pusa caspica). PLoS ONE 9: e99265.