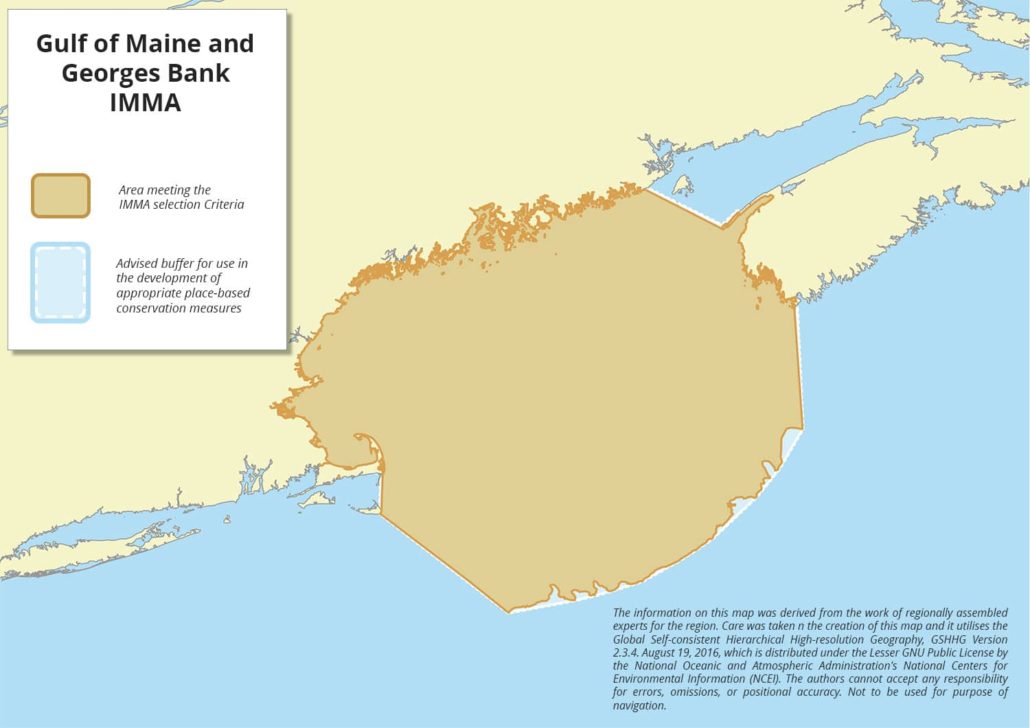

Size in Square Kilometres

148729

Qualifying Species and Criteria

North Atlantic Right Whale – Eubalaena glacialis

Criterion A; B (2); C (1, 2, 3b)

Fin Whale – Balaenoptera physalus

Criterion A; B (2); C (2)

Sei Whale – Balaenoptera borealis

Criterion A

Sperm Whale – Physeter macrocephalus

Criterion A

Common minke whale – Balaenoptera acutorostrata

Criterion B (2)

Humpback Whale – Megaptera novaeangliae

Criterion B (2); C (2)

Harbor Seal – Phocoena phocoena

Criterion C (1, 2)

Atlantic White-sided Dolphin – Leucopleurus acutus

Criterion C (2)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Balaenoptera borealis, Balaenoptera physalus, Delphinus delphis, Eubalaena glacialis, Globicephala melas, Grampus griseus, Halichoerus grypus, Leucopleurus acutus, Megaptera novaeangliae, Phoca vitulina, Phocoena phocoena, Physeter macrocephalus, Tursiops truncatus

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Balaenoptera musculus, Orcinus orca

Summary

The Gulf of Maine is a continental shelf sea off New England and southwestern Nova Scotia. It is isolated from the Mid-Atlantic Bight to the south by the Nantucket Shoals, from the Scotian Shelf to the north by Browns Bank, and from the wider Atlantic Ocean to the east by Georges Bank. Strong circulation over complex bathymetry aggregates fat-rich zooplankton, the preferred prey of North Atlantic right whales, and many forage fish preyed upon by other marine mammals in many areas in this IMMA. It encompasses some of the most important foraging habitats for marine mammals along the U.S. East Coast. Within this area there are four threatened species: North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis), sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis) fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) and sperm whales (Physeter microcephalus). This IMMA encompasses important foraging habitats, which leads to aggregations of North Atlantic right, humpback, fin and minke (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) whales. Reproductive behaviour of North Atlantic right whales has been witnessed in this IMMA and harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) breed in northwestern Gulf of Maine (GoM) waters. North Atlantic right whales perform consistent, seasonally-timed movements among specific Gulf of Maine areas. The area includes the Northeastern U.S. Foraging Area Critical Habitat for the North Atlantic right whale and the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

Four species occurring regularly with this IMMA are considered threatened with extinction according to the global IUCN Red List. The North Atlantic right (Eubalaena glacialis) whale is listed as Critically Endangered on the Red List (Cooke 2020). Sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis) are listed as Endangered on the Red List (Cooke 2018a). Fin (Balaenoptera physalus; Cooke 2018b) and sperm (Physeter microcephalus; Taylor et al. 2019) whales are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

This IMMA encompasses some of the most important foraging habitats for cetaceans in U.S. waters (Kenney and Winn 1986), which leads to aggregations of many species. It includes the highest density feeding area for North Atlantic right whales in U.S. waters: Cape Cod Bay. Modern photo-identification data of right whales in this area date back to 1959, and dedicated monitoring of right whales in this habitat has been conducted for over 20 years. Studies have demonstrated that this is an important habitat for multiple life history functions, including foraging, socialising, and as a post-calving ‘nursery’ area, where females return with their calves at the end of the breeding season (Mayo et al. 2018). In a study examining sightings data from 1998-2017, estimated right whale abundance increased over time, and abundance in peak months increased at 10%/year, much higher than the rate of increase for the overall population (Ganley et al. 2019). Over 40% of the entire population has been documented in this habitat on a single day via aerial surveys (i.e. 7 April 2019, Center for Coastal Studies).

The Gulf of Maine is the southwestern-most primary humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) feeding ground in the North Atlantic Ocean (Katona and Beard 1990, Stevick et al. 2006) and individuals aggregate there from March through December (Clapham et al. 1993, Robbins 2007). Aggregations tend to occur in areas of high bathymetric relief, such as at banks, slopes and ledges from the waters off Massachusetts to Nova Scotia. While their specific distribution varies from year to year within the IMMA, the relative density of humpback whales tends to be highest in the southwest and northeast portion of the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy (CETAP 1982, Robbins 2007).

Fin and minke (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) whales aggregate in many of the same areas used by humpback whales. Photo-identification research indicates that all three species exhibit extended occupancy in the region (Clapham and Mayo 1987, Seipt 1990, Murphy 1996) and annual return (Clapham and Seipt 1991). For both humpback and fin whales, there is also evidence that distribution and aggregation sites within the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy are influenced by demographic class (Agler et al. 1993, Robbins 2007).

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

Reproductive behaviour of North Atlantic right whales has been witnessed in this IMMA in the form of “surface active groups” (Kraus and Hatch 2001). Based on aerial survey data collected during a 7-year study, over 200 individual right whales were identified in the central Gulf of Maine, representing approximately half the population during that period. Significantly higher proportions of known reproductive males and females were present in this region during winter months compared to other areas, suggesting that this region may comprise a mating ground (Cole et al. 2013). The Gulf of Maine also represents an important area for lactating North Atlantic right whale females, many of whom return to Cape Cod Bay and the greater Gulf of Maine with their calves at the end of the calving season (Mayo et al. 2018). Between 1997 and 2013, an average of 12.7% of calves of the year were observed in Cape Cod Bay (Mayo et al. 2018).

The harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) is the most widely distributed phocid in the northern hemisphere (Desportes et al., 2010). The North Atlantic subspecies (Phoca vitulina vitulina) haulout count (not adjusted for animals in the water) is 129,200 animals, of which 15% breed in northwestern Gulf of Maine (GoM) waters (Waring et al 2015; NERC-SCOS 2022, DFO 2024). Harbour seals are distributed along the coast from the Canadian border to New Jersey. During the May to June breeding season there is a northward shift with the largest concentration of animals occurring in Maine (Gilbert et al., 2005; Waring et al., 2010). Harbor seals differ from other phocids in that they forage during lactation; the pups enter the water soon after birth and follow the female as she forages or moves between haulout sites (Boulva and McLaren 1979; Lesage et al 2004). Separation from the female during storms or in rough water can be an important source of pup mortality (Boness et al1992). Harbor seal breeding habitat in the GoM area is characterised by relatively isolated small islets, rocky ledges and reefs exposed at low tide, located in sheltered waters, but with access to relatively deep water for escape from predators (Gilbert et al 2005).

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

Strong circulation over complex bathymetry in the Gulf of Maine aggregates lipid-rich zooplankton, the preferred prey of North Atlantic right whales, and many forage fish preyed upon by other marine mammals, in areas such as Cape Cod Bay, the Great South Channel, and Jordan, Wilkinson, and Georges Basins (Record et al. 2019). Consequently, the Gulf of Maine is feeding habitat for many species of cetaceans and both species of pinnipeds that occupy the area.

North Atlantic right whales aggregate in large numbers to feed in areas such as Cape Cod Bay (Mayo and Marx 1990, Hudak et al. 2023), the Great South Channel (Beardsley et al. 1996, Kenney et al. 1995, 2001), and Jeffreys Ledge (Weinrich et al. 2000). Cape Cod Bay represents one of the most important historic and current feeding areas for the species within US waters. Right whale foraging behaviour has been extensively studied in this region via behavioural observation and biologging suction cup tags (e.g. Parks et al. 2012, Baumgartner et al. 2017, Hudack et al. 2023), often coupled with plankton sampling. Prey sampling and modelling efforts incorporating prey data have also been used to assess right whale foraging habitat throughout the region (e.g., Costa et al. 2006, Pershing et al. 2009, Sorochan et al. 2021, Meyer-Gutbrod et al. 2023).

Humpback whale feeding has also been well-studied in the southwest portion of this IMMA. Stellwagen Bank and the southern Gulf of Maine consistently attract a high density of humpback whales during spring, summer, and fall months. Humpback foraging behaviour in this area has been studied for more than four decades, and has been shown to involve a diversity of behaviours (Hain et al. 1982, Weinrich et al. 1992, Hain et al. 1995, Wiley et al. 2011, Allen et al. 2013, Ware et al. 2014). Surface observations, behavioural sequencing, biologging tags, active acoustic data collection, and oceanography have been utilised to examine humpback foraging strategies relative to demographics, conspecific behaviour, prey (type, behaviour, and densities), and oceanographic processes (e.g., Hazen et al. 2009, Wiley et al. 2011, Pineda et al. 2015). Biologging tags have also revealed acoustic behaviour associated with foraging activity (Stimpert et al. 2007).

Foraging behaviour of fin whales and Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Leucopleurus acutus) has also been documented. On 42 aerial surveys conducted by the New England Aquarium since January 2023, foraging behaviour (e.g., lunge feeding) and defecation have been observed 22 times for fin whales (New England Aquarium, unpublished data). Feeding was documented once and inferred in 9.5% (n=45) of opportunistically reported sightings of Atlantic white-sided dolphins on Stellwagen Bank and Jeffreys Ledge (Weinrich et al. 2001).

Pinnipeds forage at sea but require a solid platform for pupping, raising their young, molting, and resting. Harbor seals prefer isolated sandbars, small islets and rocky ledges and reefs exposed at low tide, all of which are distributed around the Gulf of Maine (Gilbert et al. 2005; Waring et al 2015). They prefer foraging within 20km of their haulout sites at depths of less than 100m, but deeper depths and foraging further offshore have been reported (Lesage et al 1999; Wynne-Simmonds et al 2024). They rely on diverse prey consisting primarily of gadoids such as hake (Urophycis sp.), flatfish (Pseudopleuronectes sp., Scophthalmus sp.), sandlance (Ammodytes sp.), herring (Clupea harengus, shad (Alosa sp.), menhaden (Brevoortia sp., Payne and Selzer 1989; Toth et al. 2018), all of which are plentiful in the Gulf of Maine.

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

C3a – Whale Seasonal Migratory Route

C3b – Migration / Movement Area

North Atlantic right whales perform consistent, seasonally-timed movements among specific Gulf of Maine areas (e.g., Kenney et al. 1995, Kenney et al. 2001). While calving takes place outside of this IMMA in winter, the majority of the rest of the population occupies Cape Cod Bay from winter to early spring. The population then shifts to the Great South Channel where they feed from spring to early summer. Right whales subsequently move out of this IMMA to feed in Canadian waters from summer into fall. When North Atlantic right whales return in large numbers to the IMMA, they aggregate in a possible mating ground in the central Gulf of Maine (Cole et al. 2013) as well as in a feeding area at Jeffreys Ledge (Weinrich et al. 2000) before returning to their winter Cape Cod Bay feeding ground. Although these seasonal movements involve the majority of the population, the exact routes taken within the IMMA are not clearly defined.

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

Species density modelling shows that 14 cetacean species have been recorded as present or seasonally present in the Gulf Maine and Georges Bank area, including gray seals (Halichoerus grypus), harbour seals, minke whales, fin whale, sei whale, humpback whale, right whale, long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas), Atlantic white-sided dolphins, common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncates), harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena), short-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), sperm whales, and Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) (Roberts et al. 2023). Two studies (Hodge et al. 2022; Roberts et al. 2023) have evaluated marine mammal species diversity along the entire United States East Coast. There is substantial overlap in the data sets used by both studies, but the studies used different methods to derive estimates of species diversity. Both studies found intermediate levels of species diversity in the Gulf Maine and Georges Bank area.

Supporting Information

Agler BA, Schooley RL, Frohock SE, Katona SK, Seipt IE. 1993. Reproduction of photographically identified fin whales, Balaenoptera physalus, from the Gulf of Maine. Journal of Mammalogy 74:577-587.

Allen J, Weinrich M, Hoppitt W, Rendell L. 2013. Network-Based Diffusion Analysis Reveals Cultural Transmission of Lobtail Feeding in Humpback Whales. Science 340(6131):485-488.

Baumgartner, M.F., Wenzel, F.W., Lysiak, N.S. and Patrician, M.R., 2017. North Atlantic right whale foraging ecology and its role in human-caused mortality. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 581, pp.165-181.

Beardsley RC, Epstein AW, Chen C, Wishner KF, Macaulay MC, Kenney RD. 1996. Spatial variability in zooplankton abundance near feeding right whales in the Great South Channel, Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 43: 1601-1625.

Boness, D.J., Bowen, D., Iverson, S.J., and Oftedal, O.T. 1992. Influence of storms and maternal size on mother–pup separations and fostering in the harbor seal, Phoca vitulina. Can. J. Zool. 70(8): 1640–1644. doi:10.1139/z92-228.

Boulva, J. and McLaren, I. A. 1979. Biology of the harbor seals, Phoca vitulina, in eastern Canada. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 200: 1-24.

CETAP. (1982). A characterization of marine mammals and turtles in the mid- and North Atlantic areas of the U.S. outer continental shelf, final report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Land Management.

Cole TVN, Hamilton P, Henry AG, Duley P, Pace RM, III, White BN, Frasier T. 2013. Evidence of a North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis mating ground. Endangered Species Research 21(1):55-64.

Cooke, J.G. 2018a. Balaenoptera borealis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T2475A130482064. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2475A130482064.en.

Cooke, J.G. 2018b. Balaenoptera physalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018:e.T2478A50349982. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2478A50349982.en.

Cooke, J.G. 2020. Eubalaena glacialis (errata version published in 2020). The IUCN Red List of

Threatened Species 2020: e.T41712A178589687. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-

2.RLTS.T41712A178589687.en

Desportes, G., Bjorge, Rosing-Asvid, A., & Waring, G. T. (Eds.). (2010). Harbour seals of the North Atlantic and the Baltic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 8, 377 pp. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.8

DFO. 2024. Stock Assessment of Atlantic Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina vitulina) in Canada for 2019–2021. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2024/023.

Ganley LC, Brault S, Mayo CA (2019) What we see is not what there is: estimating North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis local abundance. Endang Species Res 38:101-113. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00938

Gilbert, J. R., Waring, G. T., Wynne, K. M., & Guldager, N. (2005). Changes in abundance and distribution of harbor seals in Maine, 1981–2001. Marine Mammal Science, 21(3), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01246.x

Hain JH, Carter GR, Kraus SD, Mayo CA, Winn HE. 1982. Feeding behavior of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, in the western North Atlantic. Fishery Bulletin 80:259-268.

Hain JH, Ellis SL, Kenney RD, Clapham PJ, Gray BK, Weinrich MT, Babb IG. 1995. Apparent bottom feeding by humpback whales on Stellwagen Bank. Marine Mammal Science 11(4):464-479.

Hazen, E.L., Friedlaender, A.S., Thompson, M.A., Ware, C.R., Weinrich, M.T., Halpin, P.N. and Wiley, D.N., 2009. Fine-scale prey aggregations and foraging ecology of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 395, pp.75-89.

Hodge, B.C., Pendleton, D.E., Ganley, L.C., O’Brien, O., Kraus, S.D., Quintana-Rizzo, E., Redfern, J.V., 2022. Identifying predictors of species diversity to guide designation of marine protected areas. Conservation Science and Practice 4, e12665.

Hudak, C.A., Stamieszkin, K. and Mayo, C.A., 2023. North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis prey selection in Cape Cod Bay. Endangered Species Research, 51, pp.15-29.

Kenney RD, Winn HE. 1986. Cetacean high-use habitates of the northeast US continental shelf/slope areas. Fishery Bulletin 84:345-357.

Kenney RD, Winn HE, Macaulay MC. 1995. Cetaceans in the Great South Channel, 1979-1989: right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). Continental Shelf Research 15(4-5):385-414.

Kenney RD, Mayo CA, Winn HE. 2001. Migration and foraging strategies at varying spatial scales in western North Atlantic right whales Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (Special Issue 2):251-260.

Kraus SD, Hatch JJ (2001) Mating strategies in the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). J Cetacean Res Manag 2(Spec Issue): 237−244

Lesage, V., Hammill, M. O., & Kovacs, K. M. (1999). Functional classification of harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) dives using depth profiles, swimming velocity, and an index of foraging success. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 77(1), 74–87. https://doi.org/ 10.1139/z98-199

Lesage, V., Hammill, M.O., and Kovacs, K.M. 2004. Long-distance movements of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) from a seasonally ice-covered area, the St. Lawrence River estuary, Canada. Can. J. Zool. 82(7): 1070–1081. doi:10.1139/Z04-084.

Mayo CA, Marx MK. 1990. Surface foraging behavior of the North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, and associated zooplankton characteristics. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68(10):2214-2220.

Mayo, C.A., Ganley, L., Hudak, C.A., Brault, S., Marx, M.K., Burke, E., Brown, M.W., 2018. Distribution, demography, and behavior of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts, 1998–2013. Marine Mammal Science 34, 979-996.

Meyer‐Gutbrod, E.L., Davies, K.T., Johnson, C.L., Plourde, S., Sorochan, K.A., Kenney, R.D., Ramp, C., Gosselin, J.F., Lawson, J.W. and Greene, C.H., 2023. Redefining North Atlantic right whale habitat‐use patterns under climate change. Limnology and Oceanography, 68, pp.S71-S86.

Murphy, M.A. 1996. Occurrence and Group Characteristics of Minke Whales, Balaenoptera Acutorostrata, in Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay. Oceanographic Literature Review 43: 506–506.

Natural Environment Research Council Special Committee on Seals (NERC-SCOS). 2022. Scientific Advice on Matters Related to the Management of Seal Populations. 206 p. Scientific Advice on Matters Related to the Management of Seal Populations: 2022 (st-andrews.ac.uk).

Parks, S.E., Warren, J.D., Stamieszkin, K., Mayo, C.A. and Wiley, D., 2012. Dangerous dining: surface foraging of North Atlantic right whales increases risk of vessel collisions. Biology letters, 8(1), pp.57-60.

Payne, P.M. and L.A. Selzer. 1989. The distribution, abundance and selected prey of the harbor seal, Phoca vitulina concolor, in southern New England. Mar. Mam. Sci. 5:173-192.

Pershing, A.J., Record, N.R., Monger, B.C., Mayo, C.A., Brown, M.W., Cole, T.V., Kenney, R.D., Pendleton, D.E. and Woodard, L.A., 2009. Model-based estimates of right whale habitat use in the Gulf of Maine. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 378, pp.245-257.

Pineda, J., Starczak, V., da Silva, J.C., Helfrich, K., Thompson, M. and Wiley, D., 2015. Whales and waves: Humpback whale foraging response and the shoaling of internal waves at Stellwagen Bank. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(4), pp.2555-2570.

Robbins J. 2007. Structure and dynamics of the Gulf of Maine humpback whale population. Ph.D. thesis. University of St Andrews, Scotland. 179 pp.

Roberts, J.J., Yack, T.M., Halpin, P.N., 2023. Marine mammal density models for the U.S. Navy Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing (AFTT) study area for the Phase IV Navy Marine Species Density Database (NMSDD), Document Version 1.3. Duke University Marine Geospatial Ecology Laboratory, Durham, NC.

Sorochan, K.A., Plourde, S., Baumgartner, M.F. and Johnson, C.L., 2021. Availability, supply, and aggregation of prey (Calanus spp.) in foraging areas of the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). ICES journal of marine science, 78(10), pp.3498-3520.

Stimpert, A.K., Wiley, D.N., Au, W.W., Johnson, M.P. and Arsenault, R., 2007. ‘Megapclicks’: Acoustic click trains and buzzes produced during night-time foraging of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Biology letters, 3(5), pp.467-470.

Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.,

Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. 2019. Physeter macrocephalus (amended version of 2008 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T41755A160983555. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41755A160983555.en.

Toth, J., S. Evert, E. Zimmermann, M. Sullivan, L. Dotts, K. W. Able, R. Hagan, and C. Slocum 2018. Annual Residency Patterns and Diet of Phoca vitulina concolor (Western Atlantic Harbor Seal) in a Southern New Jersey Estuary,” Northeastern Naturalist 25(4), 611-626, (1 November 2018). https://doi.org/10.1656/045.025.0407

Townsend, D.W., 1991. Influences of oceanographic processes on the biological productivity of the Gulf of Maine. Rev Aquat Sci 5, 211–230.

Ware C, Wiley DN, Friedlaender AS, Weinrich M, Hazen EL, Bocconcelli A, Parks SE, Stimpert AK, Thompson MA, Abernathy K. 2014. Bottom side-roll feeding by humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the southern Gulf of Maine, U.S.A. Marine Mammal Science 30:494-511.

Waring, G.T., J.R. Gilbert, D. Belden, A. Van Atten, and R.A. Digiovanni. 2010. A review of the status of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in the Northeast United States of America. NAMMCO Sci. Publ. 8.191-212.

Waring, G. T., DiGiovanni, R. A., Jr., Josephson, E.,Wood, S., & Gilbert, J. R. (2015). 2012 population estimate for the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina concolor) in New England waters (NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS NE-235). U.S. Department of Commerce.

Weinrich MT, Schilling MR, Belt CR. 1992. Evidence of acquisition of a novel feeding behaviour: lobtail feeding in humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae. Animal Behaviour 44:1059-1072.

Weinrich MT, Kenney RD, Hamilton PK. 2000. Right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) on Jeffreys Ledge: a habitat of unrecognized importance? Marine Mammal Science 16(2):326-337.

Weinrich MT, Belt CR, Morin D. 2001. Behavior and ecology of the Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus) in coastal New England waters. Marine Mammal Science 17(2):231-248.

Wiley D, Ware C, Bocconcelli A, Cholewiak D, Friedlaender A, Thompson M, Weinrich M. 2011. Underwater components of humpback whale bubble-net feeding behaviour. Behaviour 148(5-6):575-602.

Wynne-Simmonds, S., Y. Planque, M. Hudon, P. Lovell, and C. Vincent. 2024. Foraging behaviour and habitat selection of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina vitulina) in the archipelago of Saint-Pierre-and-Miquelon, Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Mamm. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.13134

Downloads

Download the full account of the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (geopackage and/or geojson) for the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: