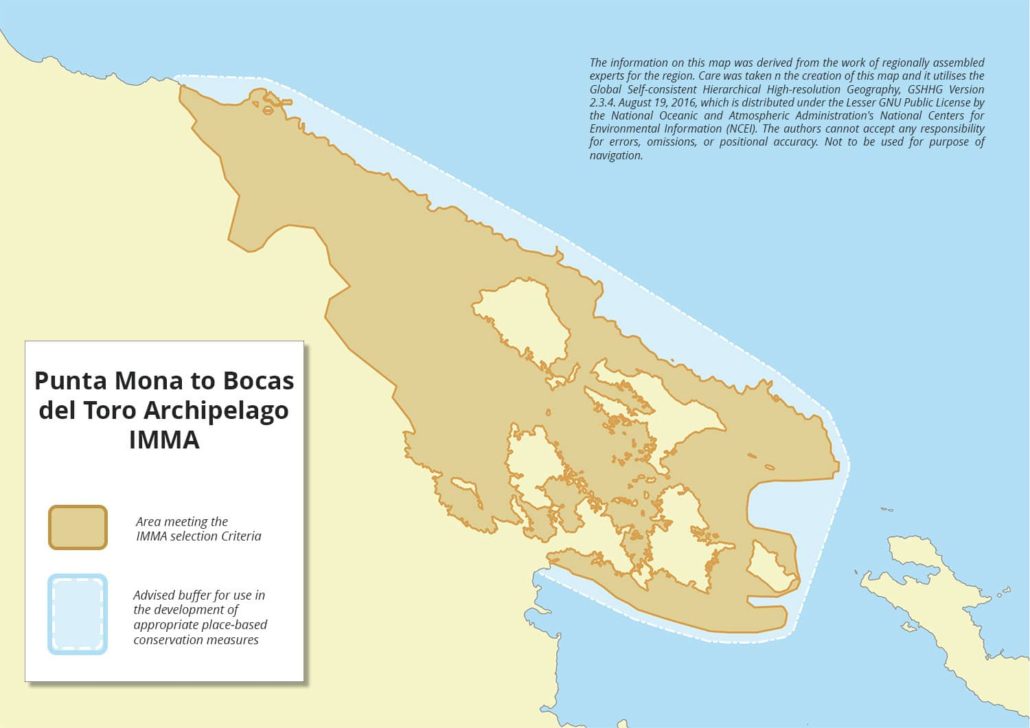

Punta Mona to Bocas del Toro Archipelago IMMA

Size in Square Kilometres

1,304

Qualifying Species and Criteria

Antillean manatee – Trichechus manatus manatus

Criterion A; Criterion C(2)

Common bottlenose dolphin – Tursiops truncatus

Criterion B(1)

Guiana dolphin – Sotalia guianensis

Criterion B(1); Criterion D(1)

Criterion D (2) – Marine Mammal Diversity

Other Marine Mammal Species Documented

Summary

The Punta Mona to Bocas del Toro archipelago IMMA is located along the Caribbean coast between Costa Rica and Panama. From the northwest to east, it extends from Punta Mona in Manzanillo to Cayo de Agua Island in the archipelago of Bocas del Toro. The northwest part of this area includes the coastal lagoons and riverine areas of Gandoca and San San Ponk Sak. This area is also influenced by the estuaries of three major rivers: Sixaola, San San, and Changuinola. The water in this habitat is murky and dark due to the presence of tannins. This portion of the IMMA is inhabited by a small, resident population of Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis), one of only two known populations in Central America. In contrast, the archipelago of Bocas del Toro consists of nine islands and multiple islets surrounded by shallow, and clear waters (less than 20 m in depth) dominated by coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests, and is home to a small and resident population of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), genetically isolated from other Caribbean populations. The inland riverine and wetland portions of the IMMA also host important feeding areas for Endangered Antillean/Greater Caribbean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus), which are known to occur in the San San and Changuinola rivers in particular. The area includes the Cahuita-Gandoca EBSA, two RAMSAR sites (the wetlands of Gandoca Manzanillo and San San Ponk Sak), and the Bastimentos Island National Marine Park, covering over 132 sq-km, and protecting coral reefs, seagrass beds, sea turtle nesting beaches, and mangrove cays.

Description of Qualifying Criteria

Criterion A – Species or Population Vulnerability

This IMMA encompasses the habitat of the Caribbean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus), recognized as the Antillean manatee by the Society for Marine Mammalogy’s Committee on Taxonomy. The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) as a species is globally assessed Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (Deutsch and Morales-Vela, 2024), but the Caribbean sub-species is considered Endangered (Morales et al. 2024). At local levels, the Caribbean manatee is also listed and protected as Endangered by the Ministry of Environment of Panama (Resolution N0. DM-0657, 2016). Self-Sullivan and Mignucci-Giannoni (2012) reported population estimates for Panama and Costa Rica at 100 individuals each, with minimum counts of 10 and 30, respectively, suggesting a critical status.

Criterion B – Distribution and Abundance

Sub-criterion B1 – Small and Resident Populations

The common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) population distributed in the archipelago of Bocas del Toro (BDT)-Panama shows high site fidelity. Mark-recapture analysis based on photo-identification data collected between 2004 and 2013 produced an abundance estimate of 80 individuals (95% CI = 72-87) (May-Collado et al., 2015). An effective population size estimate based on genetic data generated a similar abundance estimate (Ne = 73 individuals; CI = 18.0 – ∞; 0.05; Barragán-Barrera et al., 2017). A small segment of this population (37 individuals) is found in Dolphin Bay, a critical area for foraging and feeding; this segment shows a higher recapture rate compared with the rest of the population in the archipelago (May-Collado et al., 2015). Photo-ID data also show that the smaller dolphin segment in Dolphin Bay is represented by approximately 23 reproductive females producing calves (May-Collado et al., 2015).

Both males and females show high philopatry levels (Barragán-Barrera et al., 2017, May-Collado et al., 2017). This population has low mitochondrial diversity, represented by a unique mtDNA-CR haplotype, which is shared between both females and males, and it is not found anywhere else in the Caribbean (Barragán-Barrera et al., 2015, 2017; Duarte Fajardo et al., 2023). The closest neighbouring population is 35 km west of Bocas del Toro in Gandoca-Manzanillo, Costa Rica. The genetic flow between these two populations is restricted to one migrant every 10 years from Bocas del Toro to Gandoca but not the opposite (Barragán-Barrera et al., 2017). Furthermore, ecological data based on stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) and total mercury (THg) measurements suggest this bottlenose dolphin population has exclusively inshore habits, which is also reflected in the low THg levels for both females and males in the Bocas del Toro population (Barragán-Barrera et al., 2019).

Data from several surveys show that a small resident population of Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) inhabits the waters of Costa Rica between Punta Mona and Changuinola River in Panama. This is one of the two known populations of Guiana dolphins found in Central America (May-Collado et al., 2017). Using photo-identification data from 2003-2006 Gamboa-Poveda (2009) estimated a population size of about 91 (SD= 10) individuals and a residency rate of 64 photo-identified individuals’ ranged between 3 to 56%. Most recent surveys, conducted between 2022 and 2024 (May-Collado, Palacios and Kiszka, unpublished data), confirmed that there is a high residency of Guiana dolphins in this area, with less than 100 individuals identified. Unpublished data from multiple-year boat surveys between Puerto Viejo (Costa Rica) and Bocas del Toro (Panama) indicate that the Guiana dolphins only occur from Punta Mona on the Costa Rican side to the Changuinola River on the Panama side (May-Collado et al., unpublished data) and remain within 3km from the shore (Gamboa-Poveda, 2009).

Sub-criterion B2 – Aggregations

Criterion C: Key Life Cycle Activities

Sub-criterion C1 – Reproductive Areas

Sub-criterion C2: Feeding Areas

The wetland and riverine portions of the IMMA, particularly the San San and Changuinola rivers contain vegetation that provides ideal foraging areas for Greater Caribbean manatees. The composition of aquatic plants in the IMMA can vary seasonally, however, the abundance seems high to sustain individuals feeding for months and years (Guzman, 2024, unpublished data).

A satellite tagging feasibility study conducted in the San San Pond Sak Protected Area in 2012 found the following types of vegetation known to be eaten by manatees in other locations: various shore grasses (Panicum sp., Axonopus sp., and Brachiaria sp.) and small amounts of floating vegetation (Pistia stratiotes and Nymphoides sp.), as well as red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) (Gonzalez-Socoloske et al. 2015). Although tagged and released near the coastal waters of the estuary, the locations transmitted from the tagged individual female manatee from February 1 to March 17, 2008 showed that the most intensely used areas were in inland portions of the San San and Rio Negro Rivers (Gonzalez-Socoloske et al. 2015) and the authors conclude that this freshwater/brackish vegetation provides all the nutrients required by the species.

Acoustic monitoring detected manatee vocalisations for months inside the shallow wetlands surrounding the San San and Changuinola rivers, where they are presumed to be feeding (Merchan et al. 2019, 2024; Guzman 2024, unpublished data). A long term acoustic study counted and mapped manatees using side-scan sonar in the San San Pond Sak wetland, for 12 months. A total of 214 sonar transects, covering 1,731 km and detecting 1,004 manatees were used to generate density and abundance estimates. Animals were most likely to be found in the deeper narrow tributaries or the shallow lagoon near the river mouth. Abundance varied by season. A Bayesian model, using daily variance in counts, indicated that there were 22–71 animals at peak season, and 1–6 in December (Guzman and Condit, 2017).

Sub-criterion C3: Migration Routes

Criterion D – Special Attributes

Sub-criterion D1 – Distinctiveness

Due to the restricted movement and high residency, the Guiana dolphins are most likely isolated from South America. The closest known population of this species is approximately 600 km to the north, in Cayos Miskitos, Nicaragua. To the south, the population is located in the Gulf of Urabá (more than 660 km away), in the Colombian Caribbean (Caballero et al., 2018). A comparison of whistle repertoire among Guiana dolphins throughout their range suggests that the dolphins between Costa Rica and Panama produce very different whistles than those from 15 populations in South America (May-Collado, in review), supporting the hypothesis of geographical isolation between Central and South America populations occur (May-Collado and Wartzok, 2009; May-Collado, 2010).

Sub-criterion D2 – Diversity

Supporting Information

Acevedo-Gutiérrez, A., DiBerardinis, A., Larkin, S., Larkin, K., & Forestell, P. (2005). Social interactions between tucuxis and bottlenose dolphins in Gandoca-Manzanillo, Costa Rica. LAJAM 4, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00069

Barragán-Barrera, D.C., Islas-Villanueva, V., May-Collado, L.J., and Caballero, S. 2015. ‘Isolated in the Caribbean: Low genetic diversity of bottlenose dolphin population in Bocas del Toro, Caribbean Panama’. Annual report of the International Whaling Commission (ISSN 1561-0721). SC/66a/SM13.

Barragán-Barrera, D.C., Luna-Acosta, A., May-Collado, L.J., Polo-Silva, C., Riet-Sapriza, F.G., Bustamante, P., Hernández-Ávila, M.P., Vélez, N., Farías-Curtidor, N., and Caballero, S. 2019. ‘Foraging habits and levels of mercury in a resident population of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Bocas del Toro Archipelago, Caribbean Sea, Panama’. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 145: 343–356.

Barragán-Barrera, D.C., May-Collado, L.J., Tezanos-Pinto, G., Islas-Villanueva, V., Correa-Cárdenas, C.A., and Caballero, S. 2017. ‘High genetic structure and low mitochondrial diversity in bottlenose dolphins of the Archipelago of Bocas del Toro, Panama: a population at risk?’. PLoS One 12:e0189370.

Caballero, S., Hollatz, C., Rodríguez, S., Trujillo, F., Baker, C. S. (2018). Population structure of riverine and coastal dolphins Sotalia fluviatilis and Sotalia guianensis: patterns of nuclear and mitochondrial diversity and implications for conservation. Journal of Heredity: 757-770.

Carr, T., & Bonde, R. K. (2000). Tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis) occurs in Nicaragua, 800 KM North of its previously known range. Marine Mammal Science, 16(2), 447–452. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2000.tb00936.x

da Silva, V. M. F. & Best. R. C. (1996). Sotalia fluviatilis. Mammalian Species 527: 1-7.

D’Croz, L., Del Rosario, J.B., and Góndola, P., 2005. ‘The effect of freshwater runoff on the distribution of dissolved inorganic nutrients and plankton in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago, Caribbean Panama’. Caribbean Journal of Science. 41 (3), 414–429.

Deutsch, C.J. & Morales-Vela, B. 2024. Trichechus manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22103A43792740. Accessed on 15 November 2024.

Duarte-Fajardo, M.A., Barragán-Barrera, D.C., Correa-Cárdenas, C.A., Pérez-Ortega, B., Farías-Curtidor, N., and Caballero, S. 2023. ‘Mitochondrial DNA supports the low genetic diversity of Tursiops truncatus (Artiodactyla: Delphinidae) in Bocas del Toro, Panama and exhibits new Caribbean haplotypes’. Revista De Biología Tropical, 71(S4), e57291.

Edwards, H. H. and Schnell, G. D. (2001). Status and ecology of Sotalia fluviatilis in the Cayos Miskito Reservce, Nicaragua. Marine Mammal Science 17(3): 445-472.

Flores, P. A. C.; V. M. F. da Silva & Fettuccia D.C. (2018) Tucuxi and Guiana Dolphins: Sotalia fluviatilis and S. guianensis. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third Edition). Pages 1024-1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00264-8

Gamboa-Poveda, M. (2009). Tamaño poblacional, distribución y uso de hábitat de dos especies simpátricas de delfines en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Gandoca-Manzanillo, Costa Rica. Trabajo de graduación para optar por el grado de Maestría. Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. 90p.

Gonzalez-Socoloske, D., Olivera-Gómez, L.D., Reid, J.P., Espinoza-Marin, C., Ruiz, K.E. and Glander, K.E. (2015) First successful capture and satellite tracking of a West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) in Panama: feasilibity of capture and telemetry techniques. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 10(1): 52-57. https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00194

Guzman, H. M., & Condit, R. (2017). Abundance of manatees (Trichechus manatus) in a Panama wetland estimated from side-scan sonar. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 41(3), 556–565. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.793

May-Collado, L. J. (2010). Changes in whistle structure of two dolphin species during interspecific associations. Ethology. 116:1065-1074.

May-Collado, L.J. & D. Wartzok. (2009). A characterization of Guyana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) whistles from Costa Rica: The importance of broadband recording systems. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 125 (2): 1202-1213.

May-Collado, L.J., Barragán-Barrera, D.C., Quiñones-Lebrón, S.G., Aquino-Reynoso, W., 2012. Dolphin Watching Boats Impact on Habitat Use and Communication of Bottlenose Dolphins in Bocas del Toro, Panama during 2004, 2006–2010. Annual report of the International Whaling Commission. (SC/64/WW2).

May-Collado, L.J., Quiñones-Lebrón, S.G., Barragán-Barrera, D.C., Palacios, J.D., Gamboa-Poveda, M., and Kassamali-Fox, A. 2015. ‘The Bocas del Toro’s dolphin-watching industry relies on a small community of bottlenose dolphins: implications for management’. Annual report of the International Whaling Commission. C/66a/WW10

May-Collado, LJ.; M. Amador-Caballero, J. J. Casas; M. P. Gamboa-Poveda; F. Garita-Alpízar; T. Gerrodette; R. González-Barrientos; G. Hernández-Mora; D. M. Palacios; J. D. Palacios-Alfaro; B. Pérez; K. Rasmussen; L. Trejos-Lasso & Rodríguez-Fonseca, J. (2017) Chapter 12. Ecology and Conservation of Cetaceans of Costa Rica and Panama. In Advances in Marine Vertebrate Research in Latin America (M. Rossi-Santos and C. Finkl eds). Springer Press. Print ISBN: 978-3-319-56984-0; Electronic ISBN: 978-3-319-56985-7

Merchan, F., Echevers, G., Poveda, H., Sanchez-Galan, J.E. & Guzman, H.M. 2019. ‘Detection and identification of manatee individual vocalizations in Panamanian wetlands using spectrogram clustering’. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 146:1745-1757.

Merchan, F., Contreras, K., Poveda, H., Guzman, H. M., & Sanchez-Galan, J. E. 2024. Unsupervised identification of Greater Caribbean manatees using Scattering Wavelet Transform and Hierarchical Density Clustering from underwater bioacoustics recordings. Frontiers in Marine Science, 11, 1416247.

Morales-Vela, B., Quintana-Rizzo, E. & Mignucci-Giannoni, A. 2024. Trichechus manatus ssp. manatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22105A43793924. Accessed on 18 November 2024.

Mou-Sue, L. L., D. H. Chen, R. K. Bonde, and T. J. O’Shea. (1990) Distribution and status of manatees (Trichechus manatus) in Panama. Marine Mammals Science 6:234–241

Oshima, J. M & Oliveira-Santos, M. C. (2016) Guiana dolphin home range analysis based on 11 years of photo-identification research in a tropical estuary. Journal of Mammalogy, Volume 97, Issue 2, 23 March 2016, Pages 599–610, https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyv207

Secchi, E., Santos, M.C. de O. & Reeves, R.(2018). Sotalia guianensis (errata version published in 2019). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T181359A144232542. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T181359A144232542.en. Accessed on 19 April 2024.

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2014). Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs): Special places in the world’s oceans. Volume 2: Wider Caribbean and Western Mid-Atlantic Region. 86 pages.

Downloads

Download the full account of the Punta Mona to Bocas del Toro Archipelago IMMA using the Brochure button below:

To make a request to download the GIS Layer (shapefile and/or geojson) for the Punta Mona to Bocas del Toro Archipelago IMMA please complete the following Contact Form: